Successful home palliative care of a patient with terminal lung cancer and severe dementia

Junichi Danjo1*, Sonoko Danjo1 and Yu Nakamura1

1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kagawa University School of Medicine, Japan

2Miki Clinic, Kagawa University School of Medicine, Japan

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Junichi Danjo, MD, PhD

Department of Neuropsychiatry

Kagawa University School of Medicine

1750-1 Ikenobe, Miki, Kita

Kagawa 761-0793, Japan

Tel: +81 878985111

E-Mail: jdanjo@med.kagawa-u.ac.jp

Received Date: April 01, 2018; Accepted Date: April 12, 2018; Published Date: April 21, 2018

Citation: Danjo J, Danjo S, Nakamura Y (2018) Successful Home Palliative Care of a Patient with Terminal Lung Cancer and Severe Dementia. Cancer Biol Ther Oncol. Vol.2 No.1:3

Abstract

This case involved an end-stage lung cancer patient with severe dementia, complicated pressure ulcers, and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia that resulted in overcomplicated medical treatments. The family had difficulty providing care; thus, palliative care included treatment of pressure ulcers, optimized pharmacotherapy, and advanced care planning. This paper presents the patient’s organized treatment policies as delivered by the family and home care providers, including nurses, which alleviated the patient’s pain rating and the family’s care burden. Through these efforts, the patient was able to continue to live at home and receive palliative care according to her wishes until she died.

Keywords

Palliative care; Dementia; Care burden; Lung cancer; Chemotherapy; Ulcer

Introduction

Many people hope for a good death at home [1-3]; however, most Japanese die in hospitals [4], and opportunities for home deaths are decreasing due to the difficulty of providing care to end-stage patients among families, who may struggle to remain at home with a patient until he or she dies. For cases with severe physical impairment, continued palliative care may be difficult to provide, especially when additional behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) increase the family care burden [5]. Here, an end-stage lung cancer patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and severe BPSD was treated at home by family, who were struggling with her care. This case provides important information for home palliative care of patients with severe dementia.

Case Presentation

A 76-year-old female was other clinic outpatient with RA and Alzheimer-type dementia (AD). After prolonged coughing, she was found to have lung cancer with distant metastasis at many sites, including the lumbar spine. Unfortunately, she was not in a medical condition to receive curative treatment; thus, she and her family were transferred to a clinic near her home based on her desire to spend the rest of her life at home. She did not have brain at the time of her transfer.

She exhibited obvious BPSD; her mini mental state examination was 10 points and her clinical dementia rating was 2 points, thus her AD was assessed as moderate. Her RA exhibited moderate disease activity, but she had not received a certified degree-ofcare level from long-term care insurance. Her Barthel index (BI) was 60 points, her Lawton & Brody instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) scale rating was 3 points, and her pain was 1 point on the numerical rating scale (NRS). Her family’s care burden was 9 points on the Caregiver Burden Interview (i.e., the Japanese version of the Zarit). However, her ADL declined significantly, resulting in a BI of 40 points one month after her transfer. As her physical condition worsened, her BPSD increased, and she began to refuse care and medication, which significantly increased her family’s care burden to 24 points on the Caregiver Burden Interview. The family was not able to provide adequate hygiene or medication management, resulting in the patient developing pressure ulcers and a higher NRS rating of 7 points.

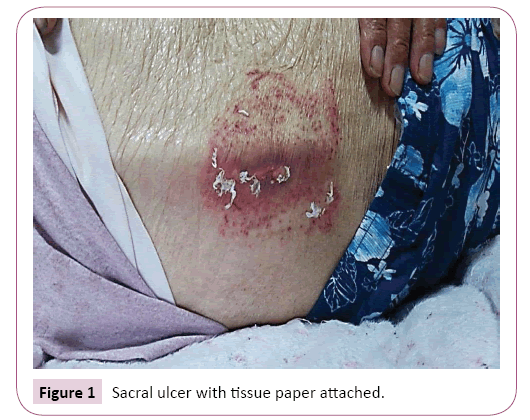

At the onset of the pressure ulcers, she began to refuse baths due to BPSD, but because she did not bath for two weeks, family and medical staff did not immediately find the pressure ulcers. The family’s care technique was rudimentary; when the abnormality on the patient’s buttocks was initially observed, the family protected the sacral ulcer with tissue paper. In Figure 1, the tissue paper had been peeled away to expose part of the decubitus, and after examination, it was found that the tissue paper had adhered to the decubitus through leachate. The family was informed of the importance of body pressure distribution by changing postures and maintaining cleanliness through bed baths, and an air mattress was added to the patient’s bed to prevent the development of additional ulcers. The pressure ulcers were treated professionally and gradually improved (Figure 2). For her increased pain, acetaminophen was gradually increased to 2,400 mg/day until her pain improved. The deterioration of her dementia and delirium was also a concern; thus, narcotics were not prescribed, but administration of analgesics and risperidone 0.5mg/day prevented her from refusing medication. Additionally, she had developed hypoalbuminemia due to poor oral intake and was prescribed enteral nutrients, and the number of nurse visits was increased.

A package of oral medicines and a medication box were provided to the family to manage the patient’s medication, which significantly improved the patient’s adherence to her medication regime. Then, treatment and care policies were organized and shared with the advance care planning (ACP) and discussed with both the family and home palliative care providers. The patient received the most severe certified degree-of-care level of 5, but the family’s care burden was alleviated (i.e., 16 points) by increasing the number of nurse visits, which also improved the patient’s NRS rating to 2 points and prevented further development of BPSD and pressure ulcers. The patient did develop herpes zoster and pneumonia but managed to continue treatment at home until her death nine months after transfer.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this case, the patient and her family hoped to continue palliative care at home, but after the emergence of complicated pressure ulcers and BPSD, the caregiver burden became significant. The patient did not want to be hospitalized or admitted to a nursing home, but her caregivers had difficulty providing adequate care at home, especially considering the patient had cancer with physical symptoms that deteriorated rapidly. In this type of situation, family caregivers often do not know how to treat patients because they lack the knowledge and skills necessary to manage treatment [5]. Here, the patient had both end-stage lung cancer and BPSD, resulting in a particularly heavy burden of care for her family. When home care burdens become too great, hospitalization or admission to a nursing home is often selected; however, ACP can also be useful for reducing a family’s care burden and allowing for longer home care periods for patients that prefer this. ACP may also be helpful for clarifying treatment policies among all caregivers. Medical staff should instruct families in patient treatment, including expected future events, such as delirium, cancer-related pain, and agonal respiration. Such efforts can bring peace of mind to patients and families, leading to longer home care periods.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 17K17925).

References

- Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Calanzani N, Cohen J, Deliens L, et al. (2006) Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: a population survey in England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann Oncol 23: 15.

- Yamagishi A, Morita T, Miyashita M,Y oshida S, Akizuki N, et al. (2012) Preferred place of care and place of death of the general public and cancer patients in Japan. Support Care Cancer 20: 2575-2582.

- Fukui S, Yoshiuchi K, Fujita J, Sawai M, Watanabe M (2011) Japanese people's preference for place of end-of-life care and death: A population-based nationwide survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 42:882-892.

- https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/suii09/deth5.html

- Gomes B, Higginson IJ (2006) Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: Systematic review. BMJ 4: 515-521.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences