Mindful Meditation on Alcohol Addiction

Ntalaja Kabuayi Philippe1,2*, Yannick Ntantu Busa1, Kasongo Christan1, Salambo Mabila Antoine1, Gerard Kongolo Wa Nzambi1, Kibokela Dalida Ndembe1, Tshangala Kavula Yves1,3, Joseph Tshitoko1 and Banzulu Degani1

1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsycho-Pathological Center/DRC, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo

2Department of Psychiatry, Dr. Joseph Guislain Neuropsychiatric Center, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

3Department of Psychiatry, Protestant University of Congo, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo

- *Corresponding Author:

- Ntalaja Kabuayi Philippe

Department of Neuropsychiatry,

Neuropsycho-Pathological Center/DRC, Kinshasa,

Democratic Republic of the Congo,

E-mail: ntalajaphilippe88@gmail.com

Received date: August 31, 2023, Manuscript No. JBBCS-23-17785; Editor assigned date: September 04, 2023, PreQC No. JBBCS-23-17785 (PQ); Reviewed date: September 18, 2023, QC No. JBBCS-23-17785; Revised date: September 25, 2023, Manuscript No. JBBCS-23-17785 (R); Published date: October 02, 2023, DOI: 10.36648/jbbcs.6.4.4290

Citation: Philippe NK, Busa YN, Christan K, Antoine SM, Nzambi GKW, et al. (2023) Mindful Meditation on Alcohol Addiction. J Brain Behav Cogn Sci Vol.6 No.4:4290.

Abstract

Mindfulness meditation is a state in which a person pays attention to their internal and external experience as it unfolds in the present moment, without judgment.

Meditation has an effect on the functioning of the brain, it leads to more intense cerebral activation of the para-limbic areas, linked to the autonomic nervous system, that is to say automatic and non-voluntary and to interoception, or perception bodily sensations. There are different practices/ methods or techniques based on mindfulness, among which we cite Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), Dialectiacal Therapy (DBT), Therapy of and Engagement (ACT) and Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP).

Patients who successfully completed the mindfulness-based programs including MBRP found themselves able to resist craving by acquiring the skill of looking at that temptation to give in or the urge without succumbing.

Keywords

Meditation; Mindfulness; Craving; Addiction; Dependence; Alcohol

Introduction

The concept of mindfulness has sparked a growing body of research in behavioral medicine over the past decade. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) was developed to prevent relapses in people suffering from depression and studies show impressive results, with a reduction in the risk of relapse of up to 50% [1].

Mindfulness meditation is a state in which a person is attentive to their internal and external experience, as it unfolds in the present moment, without judgment [2].

This form of therapy is also beginning to develop in the field of addictions and its effectiveness in reducing consumption and the risk of relapse has been demonstrated by studies carried out in the United States and is beginning to arouse some interest in Europe [3,4].

Overall, treatments based on mindfulness present interesting results for the reduction of consumption, desire and negative effects such as anxiety, depression and stress [5].

We then wanted, through a review of the medical literature and the neurophysiological bases of this method to assess its effectiveness in the management of addictions and the maintenance of abstinence with the project of applying it to our patients in a second work in the context of our country.

We based ourselves on online research of scientific articles (Pub Med, Google scholar, The Lancet, Science direct, etc.) in order to find the data necessary for writing our work.

Our general objective is to show the importance of mindfulness-based therapy in the management of alcohol addiction and the maintenance of abstinence. We have specific objectives:

• Identify the neurobiological bases of mindfulness meditation

• Check the feasibility of this therapeutic technique

Literature Review

Studies carried out

Meditation, compared to relaxation, leads to more intense cerebral activation of the para-limbic areas, linked to the autonomic nervous system, that is to say automatic and nonvoluntary and to interoception or perception of bodily sensations. As shown by the psychiatrist Rubia, from the University of London, it also activates more the fronto-parietal and fronto-limbic areas, linked to attentional capacities.

The practice of mindfulness leads to an improvement in emotional modulation, whose neural pathways are beginning to be mapped: Thus, after eight weeks of training, people in whom emotions of sadness are aroused show a lower activation of language areas (Wernicke's and Broca's areas) and greater activity in areas associated with interoceptive sensitivity. This means that the impact of sadness is more reduced, in meditators, by its “digestion” at a bodily level, than by rational, verbal processing, as happens in non-meditators [6].

Impact of mindful meditation on addiction

It has a positive action on:

• Emotional regulation

• The ability to identify negative emotions and accept them, instead of trying to modify or inhibit them

• The appeasement of ruminations

• Alleviation of depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress

• Alleviation of impulsive and rigid behaviors and alexithymia (difficulty of being aware of one's emotions).

It has been proven that people who have developed a high level of mindfulness better regulate the impact of their emotions in the face of negative events. Their emotional brain system is better regulated: The limbic system associated with emotional regulation becomes hypo-active while the frontal complex responsible for reasoning and cognition becomes hyper-active. These results cannot be generalized but they reinforce the interest of the medical profession to associate mindfulness techniques with ongoing monitoring and treatment [2].

There are several kinds of meditation, some examples of which are: sitting meditation, walking meditation, guided meditation, vipassana meditation, silent meditation, active meditation, body scan, breathwork, visualization, metta (loving kindness), spiritual meditation.

Meditation can be conceptualized as a complex family of attentional and emotional regulation training methods intended for various purposes, including the cultivation of well-being and emotional balance [7].

This approach, which one could call analytical, reflexive, also exists in the Buddhist tradition. But there is also a second, more contemplative one: Simply observing what is there. The first is an action, even if it is a mental action (thinking without distorting). The second is a simple presence, but awake and sharpened (to feel without intervening). It is she whose healing virtues are of interest to the world of psychotherapy and neuroscience [6].

Meditating is questioning your most ingrained conceptions and putting your most obvious ideas on the surface in order to study them, dissect them, strip them of their shells and try to find their heart. It is, of course, a never-ending quest. As you strip ideas of their first layers, you will refine your senses and discover new territories to explore. You will challenge your beliefs and expose them to your focus to discover the deeper aspects. You will also learn a lot about yourself, you will learn to take a step back [8].

From the Latin "Meditare" which means "to contemplate", meditation is a practice that consists of training the mind so that it frees itself from negative and harmful thoughts. Obviously, many thoughts are useful for managing one's life or solving practical problems. But the mental mechanisms are such that they constantly produce often deleterious thoughts. The objective of meditation is therefore to ensure that these thoughts no longer have control over us and to free us from our negative ruminations which prevent us from moving forward in our lives.

Mindfulness meditation is the approach used in the stress reduction workshops designed by Kabat-Zinn. There are also groups that form around experienced practitioners, especially inspired by the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Nhat Hanh who adapted the teachings of Chinese Zen (more flexible than zazen) for the West. The meeting schedule may vary from one group to another [9].

Some forms of meditation are associated with a religious quest. It is a practice that has its place in the research specific to certain religions.

Meditation is also an experience to assimilate; to meditate in this context is to make those conceptions and ideas that you discover and the ways in which you have discovered them your own. Thus, you have new tools to analyze the world, to discover your universe [8].

Mindfulness requires a quality of attention paid to the current experience, without filter, without judgment, without expectation and applies perfectly to the practice of meditation. Perceptions, emotions, cognitive phenomena must be carefully observed if not evaluated. To achieve this, it is important to get out of our habit of always judging, controlling or directing our experiences of the present moment.

It is based on two components: Self-regulation of attention and orientation to experience. It also involves 3 attentional capacities:

• Sustained attention (ability to maintain attention for a long time on a particular aspect of the experience such as breathing).

• Flexibility (ability to change one's attentional focus from one object to another in order to be able to return to the initial object of attention once a thought or image has been identified).

• Inhibition of secondary processes (ability to inhibit further, secondary, elaboration of thoughts, images or sensations) [10].

According to physician-psychiatrist Christophe André, mindfulness can be broken down into three fundamental attitudes [11]:

• The maximum opening of the attentional field

• Disengagement from judgmental tendencies, in order to control or direct your experience of the present moment

• Non-elaborative consciousness.

Mindfulness is a way of relating to one's own experience (what we perceive with the 5 senses, our bodily sensations and our thoughts). It results from the fact of voluntarily directing the attention on one's present experience and exploring it with openness, whether we find it pleasant or not, while developing an attitude of tolerance and patience towards oneself. It allows you to engage in actions in line with your values and objectives [12].

A mindful subject is one with a high intensity of awareness (better ability to observe, accept and suspend judgment on the experience in progress) [13].

Mindfulness meditation has been practiced for about 2400 years by Buddhist meditators. In the West, for Socrates and Plato (-400 BC), meditation is the primary instrument of philosophy: “Retiring into oneself allows you to think better”. Understanding the essence of things through consciousness (phenomenology) is inherent in many spiritual and religious traditions and psychological and philosophical schools of thought.

The first medical applications were developed by Dr. Kabat- Zinn of the University of Massachusetts in the 1970s. Having experienced the benefits of meditation himself as a student of Zen masters, he wanted to develop a Westernized practice and stripped of any spiritual reference, accessible to the greatest number, which he called "mindfulness". In 1979, the first “stress reduction” school was born, offering its MBSR program (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) [14].

Twenty years later, MBSR was taken over by three psychotherapist researchers, Segal, Teasdale and Williams, who were developing a depressive relapse prevention program. They supplemented the MBSR program with elements of behavioral and cognitive therapy and wrote a very detailed manual. This is how Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) emerged. Since then, this program has been declined in different adaptations for different types of problems [15].

The "Mind and Life Institute" created in 1987 and co-founded by Varella, director and researcher in cognitive neuroscience at the CNRS de la Pitié Salpêtrière, has become the reference center for "contemplative research". Other research centers exist, for example, the SINGER (System-wide Information Network for Genetic Resources) team in Germany in which Ricard participates. Many scientific works show that the regular practice of meditation can lead to real functional changes in the brain [14].

The interest of mindfulness in the field of addictions is multiple. It mainly promotes awareness of the risks of relapse through various processes [16].

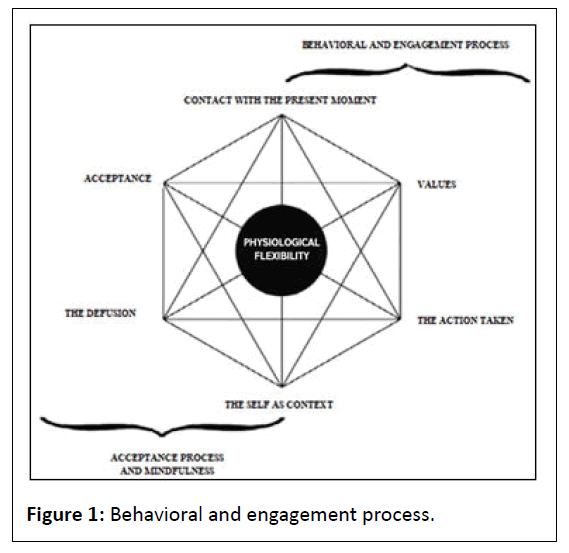

Kabbat-Zinn defines mindfulness as “a way of paying attention, intentionally, to the present moment without being judgmental”. In general, the practice of mindfulness promotes a state of metacognitive awareness allowing patients to gradually step back instead of remaining in habitual and conditioned behavior. Instead of reacting automatically by consuming in the face of a trigger, the patient can become aware of the latter and then make a choice in full consciousness on how he wishes to respond to it effectively and thus reduce the risk of relapse. In this way, patients can gradually get out of automatisms and thus restore the choice of action by adopting a “reflective” and conscious behavior rather than reacting automatically to a situation (Figure 1) [16]. Prevention and maintenance of abstinence and harm in order to avoid impulsivity and aggression.

Discussion

Several studies report interesting results with the mindfulness technique that can reduce the risk of relapse by up to 50% in alcoholics [17,18].

According to Dackwar et al., a low level of mindfulness is common among populations with addiction to psychoactive substances in general [17].

According to a review published in 2011, it was found that the majority (five out of six) of the mindfulness-based interventions were effective in reducing the consumption of the product and this, in a significant way [19,20].

Another review including 24 studies also showed significant results among users of cannabis, alcohol, cocaine, amphetamine or opiates.

For Brewer et al who carried out a randomized controlled pilot study, which, despite a small number, suggested that the MBRP program was as effective as CBTs (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy). It should be remembered that, to date, CBTs are recognized as one of the forms of psychotherapy that have best shown their effectiveness in addictions [20].

It should be noted that interventions based on mindfulness are more effective when they are carried out frequently. Indeed, the more an individual practices this technique, the less he is led to feel the sensation of craving [3].

According to a study aimed at evaluating the MBRP program which was carried out in France and which consisted of an exploratory, non-randomized, non-controlled pilot study, carried out among 26 alcohol-dependent patients divided into three groups, the first results suggest that the technique MBRP is associated with reduced alcohol consumption and lower impulsivity.

The study, conducted by Carpentier et al., assesses the impact of mindfulness in a relapse prevention group with alcoholdependent patients [21]. They sought to highlight the mechanisms of action correlated with the benefits and efficacy of MBRP. For this, they used the protocol by assessing alcohol consumption, mindfulness, impulsivity, automatic thoughts, anxiety and the ability to “cope”.

Thus, 26 patients followed an MBRP protocol for which they were divided into three distinct groups. They were asked about their alcohol consumption before and after the MBRP program follow-up.

The results show sustained abstinence or moderation of consumption leading to abstinence. Their tendency to give in to impulses decreases and their tolerance for anxiety increases. In addition, this study confirms that MBRP also increases selfefficacy and the feeling of self-efficacy [21].

Conclusion

The use of mindfulness in the care of addictology patients, particularly those with an addiction to alcohol, has shown a certain and legitimate effectiveness of great hopes for the care of dependent patients.

Patients who successfully completed the mindfulness-based programs including MBRP found themselves able to resist craving by acquiring the skill of looking at the temptation to give in or the urge without succumbing.

In other words, mindfulness equips its practitioners with the ability to manage their emotions and urges without having to give in to them by removing or inhibiting automatic consumption behaviors and favoring mindful decision-making behaviors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contribution of the Authors

All the authors contributed to the conduct of this work. They declare to have read it and approved the final version.

References

- Lilja JL, Broberg M, Norlander T, Broberg AG (2015) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Primary care patients’ experiences of outcomes in everyday life and relapse prevention. Psychology 6: 464‑477.

- (2020) Mindfulness meditation: Definition and principles.

- Hammerstein CV, Miranda R, Aubin HJ, Romo L, Khazaal Y, et al. (2018) Mindfulness and cognitive training in a CBT-resistant Patient with gambling disorder: A combined therapy to enhance self-control. J Addict Med 12: 484-489.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Skanavi S, Laqueille X, Aubin HJ (2011) Mindfulness-based interventions for addictive disorders: A review. Enceph-Rev Psychiatr Clin Biol Ther Enceph 37: 379‑387.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Id H Mindfulness and addictions: evaluation of the MBRP program (Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention) in patients presenting with or without substance addiction. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Christophe André. mindfulness meditation, Brain & Psycho - n° 41 September - October 2010[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ (2008) Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn Sci 12(4): 163-169.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Fabien (2023) What is meditation?

- (2023) Meditation.

- The Passeport Santé team (2016) Mindfulness.

- (2023) How to do meditation?

- Foreword (2003) Mindfulness.

- Trousselard M, Steiler D, Claverie D, Canini F (2014) The history of mindfulness put to the test of current data from the literature: Outstanding questions. The Brain 40(6): 474-480.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- (2023) What is meditation.

- (2023) French-speaking site on mindfulness in psychotherapy.

- Nallet A, Briefer JF, Perret I (2015) Mindfulness in addiction therapy. Rev Med Switzerland 480: 1407‑1409.

- Dakwar E, Mariani JP, Levin FR (2011) Mindfulness impairments in individuals seeking treatment for substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 37: 165-169.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Skanavi S, X Laqueille, HJ Aubin (2011) Mindfulness based interventions for addictive disorders: A review. The Brain 37: 379-387.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Chiesa A, Serretti A (2014) Are mindfulness-based interventions effective for substance use disorders? A systematic review of the evidence. Subst Use Abuse 49: 492-512.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Brewer JA, Sinha R, Chen JA, Michalsen RN, Babuscio TA, et al. (2009) Mindfulness training and stress reactivity in substance abuse: Results from a randomized, controlled, phase I pilot study. Abuse subst 30: 306‑317.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Carpentier D, Romo L, Bouthillon-Heitzmann P, Limosin F (2015) Mindfulness-Based-Relapse Prevention (MBRP): Evaluation of the impact of a group of mindfulness therapy in alcohol relapse prevention for alcohol use disorders. The Brain 41: 521‑526.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences