ISSN : 2348-9502

American Journal of Ethnomedicine

Ethnopharmacobotany of Terreiro People in Salvador City, Bahia, Brazil

Alex Sander Lopes da Silva1*, Maria Luiza Silveira de Carvalho2 and Clicia Maria de Jesus Benevides1

1Department of Life Sciences, State University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil

2Department of Biology, Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil

- *Corresponding Author:

- Alex Sander Lopes da Silva

Department of Life Sciences,

State University of Bahia, Salvador,

Brazil,

E-mail: sanderlopes@gmail.com

Received date: April 13, 2023, Manuscript No. IPAJE-23-16367; Editor assigned date: April 17, 2023, PreQC No. IPAJE-23-16367 (PQ); Reviewed date: April 28, 2023, QC No. IPAJE-23-16367; Revised date: May 08, 2023, Manuscript No. IPAJE-23-16367 (R); Published date: May 15, 2023, DOI: 10.36648/2348-9502.10.1.7946

Citation: da Silva ASL, de Carvalho MLS, de Jesus Benevides CM (2023) Ethnopharmacobotany of Terreiro People in Salvador City, Bahia, Brazil. Am J Ethnomed Vol.10 No.1: 7946.

Abstract

The prospection of drugs at from plants cited in ethnological studies has demonstrated promising results. Salvador city is an important center of knowledge inherent to Afro-Brazilian peoples and their syncretism with traditional Amerindian and European knowledge, making it an important place for ethnopharmacobotanical studies. In this context, the present work aimed to carry out an ethnopharmacobotanical survey of medicinal and Unconventional Food Plants (UFPs) used by Terreiro people in Salvador city and compare it with data from the scientific literature, in addition to comparing the similarity of data from Terreiros by religion and phytophysiognomies of your location. The snowball sampling methodology was used. Botanical identification was performed. Members of nine Terreiros of Candomblé and Umbanda were interviewed, located in the Administrative Region Boca Rio (RA-IX), Pituba (RA-VIII) and Brotas (RA-V) in the city of Salvador city in which 56 species were cited as medicinal plants and 18 as UFPs. Respondents reported getting the plants at street markets (46,23%), in the backyards (46,23%) and in the woods (7,55%) and the most used part was the leaves (62,71%). It has been observed a significant congruence of the uses cited by the interviewees with the scientific data from the consulted literature. The interviewees presented traditional knowledge about medicinal plants and UFPs with a high alignment with the scientific evidence presented, despite the scarcity of clinical studies for most species and the low number of in vivo studies.

Keywords

Medicinal plants; UFPs; Terreiro people

Introduction

The prospection of drugs and bioactive compounds at from plants cited in ethnological studies has demonstrated promising results [1,2]. Brazil represents one of the countries with the greatest biodiversity in the world, thus having an immense potential, as yet unexplored, for the prospecting of plantderived drugs, with special attention to plants used by traditional communities that still make extensive use of plants for medicinal purposes, such as Terreiro people.

Terreiro people are traditional peoples of African origin with traditional knowledge, practices and customs focused on Afrodescendant religiosity who gather in physical spaces called Terreiros (shrine houses), where their religious and cultural activities take place [3,4]. It must be considered that, in the sociocultural and religious context of these communities, health promotion takes place through a holistic perception, in the mental, physical and spiritual dimensions, generally seen in an inseparable way [5,6].

Unconventional Food Plants (UFPs) are also often part of the daily lives of people in Terreiros. UFPs are plants, or parts thereof, that despite having food and cultural relevance for traditional populations, are not usually used by local society, do not have a highly organized production chain and do not present a significant commercial interest on the part of the local agricultural industry [5-7]. UFPs are important not only as new possibilities for promoting the reduction of food insecurity, but also for the study of bioactive substances with the potential to promote health, in addition to the nutritional aspect.

The city of Salvador has been called Black Rome and Black Mecca, not only because it has the largest black population outside Africa, but also because it is a center of religious cults from African, Amerindian and European cultural and religious syncretism [8,9]. Among these Afro-Brazilian cults, Candomblé and Umbanda stand out.

Candomblé originated through the fusion of several African religious systems, when enslaved people of different ethnic groups from Africa were grouped together in the hostile environment of captivity in Brazilian lands. Possibly, due to the need to maintain cultural identity, to promote social support and cure for their illnesses, in addition to religious exercise, a system of symbiosis between gods from different pantheons emerged, syncretizing beliefs and deities according to the members who made up their communities [10]. This religion is based on the cult of Orishas, ancestral entities that merge with the forces of nature [11] and its rituals are practiced in houses, fields, forests, waterfalls or Terreiros through songs, dances, drumbeats, offerings of vegetables, minerals and not infrequently, the sacrifice of animals [12]. Plants are of vital importance for the worship of all Orishas and there is also a specific Orishas for the cult of leaves and medicinal and liturgical herbs, Ossian, as well as preserved natural spaces, for holding specific services and collecting sacred plants.

Umbanda, on the other hand, is cited as the only genuinely Brazilian religion, as it was officially created at the beginning of the 20th century, by Zélio Fernandino de Moraes in 1908, in the suburbs of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, based on religions of African origin, catholicism and in spiritism [12]. Saraceni, et al., however, cites the existence of previous similar manifestations, such as the Umbanda line, which were presented in Candomblé sheds, since the mid-nineteenth century [13]. Other authors also point out the strong similarity between Umbanda and Cabula, a syncretic religious movement created in Bahia and present in Rio de Janeiro in the 19th century, involving elements of Afro-Brazilian cults and spiritist philosophy, quite similar to Umbanda, which Pembas, candles and the presence of cambones are also used, figures that help supporters during trance [10-14]. From African roots, Umbanda maintains, among other aspects, the cult of the Orishas and the elements of nature, the use of plants for liturgical and medicinal purposes and mediumistic trances.

The present study aimed to carry out a survey of medicinal plants and UFPs used by people from Candomblé and Umbanda Terreiros in the city of Salvador, to compare popular medicinal uses with already established scientific data on their potential pharmacological activities and the similarity between the data obtained in the different Terreiros, in order to provide a greater understanding of traditional knowledge about these plants and their use for medicinal and food purposes.

Materials and Methods

Study area

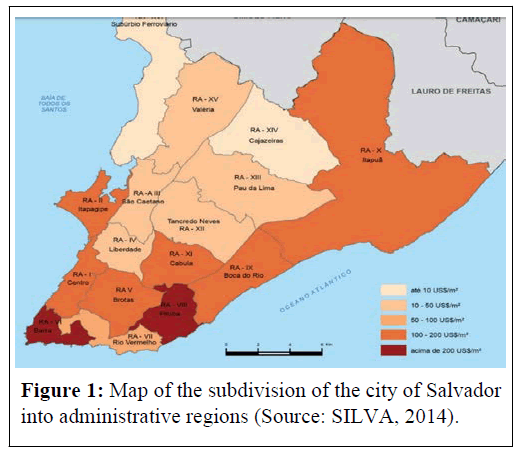

The municipality of Salvador, capital of the state of Bahia, Brazil, is located at the geographic coordinates 12°58'13" South and 38°30'45" West. The subdivision of the municipality into administrative regions was used, as described in Municipal Law 6,897/2005 (Figure 1), in order to facilitate and order the delimitation of the study area.

The city has areas of vegetation predominantly formed by remnants of native Atlantic Forest, one of the most threatened Brazilian biomes, due to extensive human action, the expansion of agricultural, extractive, livestock and mining activities and in large urban centers, as in the case of Salvador, mainly due to real estate speculation [15]. The Restinga and the Mangroves are two important ecosystems, associated with the Atlantic Forest and also present in the municipality of Salvador, the first being a set of coastal plains covered by marine deposition, with vegetation adapted to saline and sandy conditions, with creeping herbaceous species, endowed with of broad root systems and the second a coastal ecosystem of transition between terrestrial and marine environments subject to the daily action of the tides, dominated by typical plant species, being associated with the meeting of river waters with those of the sea [16].

As reported by Santos, et al., [15], the rich biological diversity of the biome, still little studied, harbors a promising area of research for the prospection of drugs and biologically active compounds.

Sample design, data collection and principles of inclusion and exclusion

The sample design was based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and the inclusion criteria were: In terms of location, the Candomblé and Umbanda Terreiros located in RA-V, RA-VIII and RA-IX in Salvador and within of these, only plants used for food and/or medicinal purposes, even if associated with liturgical or spiritual purposes. Also, only Terreiros whose representatives declared their acceptance of participation, via letter of consent and whose interviewed member had signed the Free and Informed Consent Term (FPIC) participated in the sampling.

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were location outside the predefined locus, other religions of African origins, Terreiros whose representatives refused to participate in the study, or whose leaders refused to sign the free and informed consent term. With regard to plants, those not considered UFPs and/or medicinal were excluded.

After approval by the local Research Ethics Committee (REC), to obtain the primary data, a qualitative and quantitative exploratory model was chosen through the snowball sampling methodology, a non-probabilistic method, in which the initial participants of a study indicate new participants, through a chain of reference, or network of contacts, until the proposed objective is reached, maintaining the scope of the study area and the principles of inclusion and exclusion. The ethnobotanical information about the place of collection and the categorization of plants with medicinal and/or food use in liturgical services came from semi-structured interviews, with representatives of each of the participating Terreiros, as indicated by the members of the community, with only one interview per Terreiro, between July 2021 and July 2022 [17]. The interviews were transcribed and the scripts consisted of open questions and addressed socio-cultural aspects and the ethnopharmacobotanical knowledge of the representatives of the respective Terreiros.

Obtaining plants, identification and statistical analysis

The collection of fertile samples was tentatively carried out in the places indicated by the interviewees of each participating Terreiro, or by other members, as indicated by the interviewee, in order to obtain material for deposit in collection and identification at the lowest taxonomic level possible. The collected samples were processed according to usual herborization methods [18] and registered in the Alexandre Leal Costa Herbarium of the Federal University of Bahia (ALCB). When no fertile material was obtained, the record was made through photographs of the plants in loco. The identification of materials was carried out based on specific literature, primarily indicated by do Brasil, et al., [19], where all the scientific names of the species were also checked.

For a better characterization of the plants as a function of the variables, the multivariate statistical analysis of clustering (cluster analysis) was used through presence and absence matrix for analysis of similarity through the statistical software PAST®. In addition, the results of the identification of plants (family and taxon), locations of obtaining and parts of the plant used were analyzed in terms of frequency of occurrence in the different Terreiros, with percentage analysis using the statistical software STATA® version 14.

Finally, the therapeutic indications of each plant mentioned in the ethno-directed interviews, the respective phytochemical compounds and pharmacological tests (in vitro, in vivo, ex vivo and clinical) that can support the discussion of the therapeutic use of plants by the interviewees, as well as the nutritional components and bioactive phytochemicals that can bring benefits in relation to the consumption of the mentioned UFPs..

Results and Discussion

Characterization of respondents

Leaders of nine Terreiros in Salvador city were interviewed, four from Umbanda and five from Candomblé (of these, four from the Ketu nation and one from the Angola nation). Regarding the geographical distribution, thirty-five Terreiros were contacted, of which twenty-six ceased communications for the progress of the research or refused to participate, citing several reasons, among the main ones: Suspension of activities due to the Covid-19 pandemic, incompatibility of agenda and cult secrets (considering that, in the universalist view, herbs must have their “asè” ritualistically activated for their use, through sacred words, prayers, chants and other religious activities, restricted to initiates, some of which are of these plants considered inappropriate for a person, depending on their ruling Orisha, transmitting only medicinal knowledge would, in the view of some leaders, a cultural and religious mischaracterization).

The mean age of the participants was 49.67 ± 14.97 years and the mean time in religion was 26.53 ± 20.11 years. As for gender, 55.56% of respondents were women and 44.44% were men. All interviewees reported having experience in the Terreiro as the main source of their learning.

Place of obtaining the plants and used parts thereof

The places where medicinal plants are obtained are important, as they can affect their correct botanical identification, their phytochemical composition and be correlated with the presence of contaminants.

The main places for obtaining medicinal plants were fairs and backyards, whether in the Terreiro itself, members or neighbors (46.23% each) and the forest (7.55%). Obtaining plants at fairs raises a concern about the correct botanical identification of the species used, because, as plants are often sold already dried and crushed, even an experienced person would have difficulty identifying exchanges. Another warning factor is the origin and hygienic-sanitary conditions of handling, transport and storage, which can lead to significant contamination. One hypothesis for why plants are now obtained at fairs is the high real estate pressure in urban centers, which has considerably reduced the size of Terreiros, many of which no longer have space to grow them, as well as its members, as well as the reduction of native forest fragments, which are both a source of plants for medicinal, food and ritual purposes, as well as a place of worship. The low percentage of collection in the forests may be a natural reflection in the urban context of a large metropolis, however, it may also reflect a low environmental preservation of native forest fragments and the high sociocultural, environmental and religious impact that this represents.

The parts of the plants most used for making homemade medicines were leaves (62.71%) and flowers (15.25%), followed by the inner bark, stem or stalk, bark, fruits and seeds (3.39% each) and finally, the roots, resins and bulb (1.69%). These results corroborate a popular phrase said by practitioners of African religions in Brazil, which is "there is no life without leaves, there is no Orisha without leaves" and which demonstrates the importance of plants and their leaves for these traditional communities [20].

Characterization of medicinal plants

Based on the data obtained in the interviews, 56 species were cited for medicinal purposes (Table 1).

| Botanical classification | Commom name | Popular indications of use | Used part | Obtaining place | Preparation | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoxaceae | ||||||

| Sambucus nigra (L.) | European elder | Flu like symptoms | Leaves | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Alliaceae | ||||||

| Allium sativum (L.) | Garlic | Cough, flu like symptoms | Bulb | Fair (3) | Infusion | 3 |

| Allium cepa (L.) | Yellow onion | Arterial hypertension | Barks | Fair (2) | Infusion | 2 |

| Aloaceae | ||||||

| Aloe vera (L.) | Babosa | Wound healing, gastritis, ulcer, stomach pain | Leaves (gel) | Fair (1) | In natura | 3 |

| Backyard (2) | ||||||

| Amaranthaceae | ||||||

| Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants | Mexican tea | Gastrointestinal diseases, worms, flu like symptoms and injuries | Leaves | Fair (2) | Maceration | 5 |

| Backyard (2) | ||||||

| Anacardiaceae | ||||||

| Schinus terebinthifolia (Raddi) | Aroeira | Anti-inflammatory, healing, gynecological diseases | Barks | Backyard (3); | Decoction (bark) | 7 |

| Leaves | Woods (3); Fair (1) | Infusion (leaves) | ||||

| Annonaceae | ||||||

| Annona muricata (L.) | Soursoap | Arterial hypertension | Leaves | Backyard | Infusion | 1 |

| Apiaceae | ||||||

| Angelica archangelica (L.) | Angelica | Calming | Flowers | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Pimpinella anisum (L.) | Fennel | Stomach diseases, indigestion, gas and cramps intestinais | Seeds | Fair (3) | Infusion | 3 |

| Asteraceae | ||||||

| Vernonia condensata Barker | Alumã | Digestive problems, antidiarrheal | Leaves | Backyard | Infusion | 1 |

| Arnica sp. (L.) | Arnica | Rheumatic ache | Leaves/flowers | Fair | Topical tincture | 1 |

| Matricaria recutita (L.) | Chamomile | Soothing | Flowers | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Blanchetia heterotricha DC. | Maria-preta | Flu and breathing diseases | Leaves | Fair(1); Backyard(1) | Syrup | 2 |

| Burseraceae | ||||||

| Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) | Amescla | Heart problems, glaucoma, stimulant | Leaves | Backyard | Infusion | 1 |

| Commiphora myrrha (Nees) | Myrrh | Aches, inflammation and throat infection | Resin | Fair | Tincture | 1 |

| Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J.B. Gillett | Umburana | Anti-inflammatory | Leaves | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Celastraceae | ||||||

| Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. ex Reissek | Espinheira-santa | Gastritis, stomach pain, ulcers and gynecological diseases | Leaves | Fair (1) | Infusion | 2 |

| Woods (1) | ||||||

| Costaceae | ||||||

| Costus spicatus Swartz | Cana-de-macaco | Urinary infections | Leaves | Backyard | Infusion | 1 |

| Crassulaceae | ||||||

| Kalanchoe brasiliensis Cambess and Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. | Miracle leaf | Body swelling, stomach pain, intestinal problems, eye irritation, inflammation, excess ear wax and hemorrhoid treatment | Leaves (Juice) | Backyard (6) | In natura | 6 |

| Euphorbiaceae | ||||||

| Euphorbia tirucalli (L.) | Pencil cactus | Wart treatment | Stalk (sap) | Backyard | In natura | 1 |

| Fabaceae | ||||||

| Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) | Barbatimão | Gynecological and psychiatric diseases | Barks | Fair | Decoction | 1 |

| Clitoria ternatea (L.) | Asian pigeonwings | Diabetes and insulin resistance | Flowers | Backyard | Infusion | 1 |

| Humiriaceae | ||||||

| Endopleura uchi (Huber) Cuatrec. | Uxi-amarelo | Fibroids treatment, antitumor, female infertility treatment | Barks | Fair | Decoction | 1 |

| Lamiaceae | ||||||

| Rosmarinus officinalis (L.) | Rosemary | Mood stabilizer | Leaves | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Lavandula sp. (L.) | Lavender | calming, sedative, colic | Flowers | Fair(1); Backyard(1) | Infusion | 2 |

| Melissa oficinalis (L.) | Lemon balm | Calming, sedative | Leaves | Backyard (3) | Infusion | 3 |

| Mentha x piperita (L.) | Peppermint | Gas, intestinal and stomach pain, flu-like symptoms | Leaves | Backyard (2) | Infusion | 2 |

| Mentha spicata (L.) | Common mint | Gas, intestinal and stomach ache, flu-like symptoms | Leaves | Fair(1); Backyard(1) | Infusion | 2 |

| Ocium basilicum (L.) | Basil | Inflammation, physical and mental exhaustion | Leaves | Fair(1); Backyard(1) | Infusion | 2 |

| Ocium gratissimum (L.) | African basil | Sinusitis, nasal congestion, hypertension | Leaves | Backyard (2) | Infusion | 2 |

| Plectranthus barbatus (Andrews) | Tapete-de-Oxalá | Stomach and digestive problems | Leaves | Fair(1); Backyard(2) | Maceration | 3 |

| Lauraceae | ||||||

| Laurus nobilis (L.) | Bay leaf | Digestive problems and arterial hypertension | Leaves | Fair (2) | Infusion | 2 |

| Melastomataceae | ||||||

| Miconia albicans (Sw.) DC. | Canela-de-velho | Rheumatic ache | Leaves | Woods | Infusion or maceration | 1 |

| Menispermaceae | ||||||

| Cissampelos fasciculata Benth | Erva-mãe-boa | Gynecological diseases | Leaves | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Monimiaceae | ||||||

| Peumus boldus Molina | Boldo | Digestive problems | Leaves | Backyard (4) | Infusion | 4 |

| Myristiaceae | ||||||

| Myristica fragrans Houtt | Nutmeg tree | Arterial hypertension | Seeds | Fair (2) | In natura (grated) | 2 |

| Myrthaceae | ||||||

| Psidium cattleyanum Sabine | Strawberry guava | Intestinal cramps and diarrhea | Leaves | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Eucalyptus sp. | Eucalypt | Breathing diseases | Leaves | Woods (3) | Nebulization | 3 |

| Eugenia uniflora (L.) | Pitanga | Flu and colds, various infections of the respiratory tract and immunostimulant | Leaves | Backyard (3) | Infusion | 3 |

| Phyllantaceae | ||||||

| Phyllanthus sp. | Stonebreaker | Kidney stone | Leaves | Backyard (2) | Infusion | 2 |

| Phytolaccaceae | ||||||

| Petiveria alliacea (L.) | Guinea | Anti-inflammatory and analgesic | Leaves | Fair (2) | Infusion | 2 |

| Piperaceae | ||||||

| Piper umbellatum (L.) | Capeba | Muscle aches | Leaves | Backyard | Hot dressing | 1 |

| Peperomia pellucia Kunth | Pepper elder | Eye irritation and gynecological diseases | Leaves | Backyard(1); Fair(1) | In natura; Infusion | 2 |

| Poaceae | ||||||

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf. | Lemongrass | Stomach problems, insomnia, flu, cough and breathing problems and general flu-like symptoms | Leaves | Fair(3); Backyard(2) | Infusion | 5 |

| Cymbopogon nardus (L.) Rendle | Citronella | Mosquito repellent | Leaves | Backyard | Maceration | 1 |

| Punicaceae | ||||||

| Punica granatum (L.) | Pomegranate | Throat infections, tonsillitis, canker sores, hair loss | Fruit | Fair(1); Backyard(1) | Decoction | 2 |

| Rosaceae | ||||||

| Rosa alba (L.) | White rose | Anti-inflammatory and soothing | Flowers | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Rubiaceae | ||||||

| Uncaria tomentosa (Willd. ex Schult.) DC. | Unha-de-gato | Antibiotic and antitumor | Stem | Fair | Decoction | 1 |

| Rutaceae | ||||||

| Ruta graveolens (L.) | Common rue | Inflammations and colic | Leaves | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Citrus limon (L.) Burm F. | Sicilian lemon | Stimulant, immunomodulator, flu-like symptoms | Fruit | Fair (2) | Decoction | 2 |

| Citrus × sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Orange tree | Calming, nausea and stomach pains | Flowers | Fair (2) | Infusion | 2 |

| Citrus reticulata Blanco | Tangerine tree | Anxiety and insomnia | Leaves | Fair | Infusion | 1 |

| Solanaceae | ||||||

| Cestrum sp. | Lady of the night | Muscle aches | Leaves | Backyard | Hot dressing | 1 |

| Solanum americanum Miller | American black nightshade | Healing | Leaves | Fair | Maceration | 1 |

| Zingiberaceae | ||||||

| Zingiber officinale (Roscoe) | Ginger | Stimulant and immunomodulator | Root | Fair | Decoction | 1 |

| Alpinia zerumbet (Pers.) | Shell ginger | Insomnia, anxiety and heart diseases | Flowers | Backyard (2) | Infusion | 2 |

Table 1: Medicinal plants cited by respondents from Candomblé and Umbanda Terreiros.

The most cited medicinal plants were Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi, Kalanchoe sp. (K. brasiliensis cambess and K. pinnata (Lam.) Pers.), Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf and Mosyakin& Clemants and Peumus boldus Molina. Most usage citations are for the resolution of minor health problems, such as inflammation, injuries, flu-like symptoms and blood glucose and hypertension control; however, there are also citations for cancer treatment. Medicinal plants or herbal medicines produced from them can be an important form of treatment for self-limiting health problems, especially in regions where the public health system does not have many medicines to dispense to patients. In addition, phytochemical screening and pharmacological assays can be useful for prospecting and isolating substances of medical interest.

The families with the highest representation of species in the interviewees' citations were Lamiaceae, Asteraceae, Rutaceae, Burseraceae and Myrthaseae. The Lamiaceae and Asteraceae families also appear as the two most representative families in the study by Pagnocca, et al., [4] carried out in the African matrix communities of the Island of Santa Catarina and appear as the third and second, respectively, most cited in the systematic review by Silva and collaborators, et al., [21] on ethnopharmacological studies carried out in Brazil during the 21st century. These data are in agreement with the most representative botanical families in number of species mentioned in the pharmacopoeias of several groups native to South America, according to Bennett; Pance, et al., Lamiaceae, Asteraceae, Poaceae, Fabaceae, Malvaceae, Rutaceae and Apiaceae. Of these, only species of the Malvaceae family were not mentioned in the present study, while the families Burseraceae and Myrthaceae, two of the most cited families in this study; do not appear in the list of the most cited in South America by Bennett; Pance, et al., [22].

Table 2 presents the popular use of the plants mentioned by the interviewees and findings in the literature, in studies of pharmacological activity that may corroborate these indications for use.

| Characterization of plants and claim of biological activity | Studies with positive evidence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botanical classification | Common name | Popular indications of use | In vitro | In vivo ou ex vivo | Clinicals |

| Adoxaceae | |||||

| Sambucus nigra (L.) | European elder | Flu-like symptoms | Zakay-Rones, et al., [23] | Mahboudi, et al., [24] | |

| Alliaceae | |||||

| Allium sativum (L.) | Garlic | Cough, flu like symptoms | Rouf, et al., [25] | Lissimman, et al., [26] | |

| Allium cepa (L.) | Yellow onion | arterial hypertension | Naseri, et al., [27] | Naseri, et al., [27] | |

| Aloaceae | |||||

| Aloe vera (L.) | Babosa | Wound healing, gastritis, ulcer, stomach pain | Jettanacheawchankit, et al., [28] | Langmead, et al., [29] | |

| Amaranthaceae | |||||

| Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin&Clemants | Mexican tea | Gastrointestinal diseases, worms; | Monzote, et al., [30] | ||

| Flu like symptoms and injuries | Trivellatograssi, et al., *[31] | ||||

| Anacardiaceae | |||||

| Schinus terebinthifolia (Raddi) | Aroeira | Anti-inflammatory, healing | Cavalher-Machado, et al., [32]/Ribas, et al., 2006 [33] | ||

| Gynecological diseases | Lucena, et al., [33] | Amorim, et al., [34] | |||

| Annonaceae | |||||

| Annona muricata (L.) | Soursoap | Arterial hypertension | Sokpe, et al., [35]/Oridupa, et al., 2021 [36] | ||

| Apiaceae | |||||

| Angelica archangelica (L.) | Angelica | Calming | Kumar, et al., [37]/Kumar, et al., [38] | ||

| Pimpinella anisum (L.) | Fennel | Stomach diseases, indigestion, gas and cramps intestinais | Al Mofleh, et al., [39] | Ghoshegir, et al., [40] | |

| Asteraceae | |||||

| Vernonia condensata Barker | Alumã | Digestive problems | Silva, et al., [41] | Boeing, et al., [42] | |

| antidiarrheal; | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Arnica sp. (L.) | Arnica | Rheumatic ache | Lyss, et al., [43] | Widrig, et al., [44] | |

| Matricaria recutita (L.) | Chamomile | Calming | Viola, et al., [45]/Bozorgmehr, et al., [46] | ||

| Blanchetia heterotricha DC | Maria-preta | Breathing problems and flu | --- | --- | --- |

| Burseraceae | |||||

| Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) | Amescla | Cardiac diseases | Mobin, et al., *[47]/Carvalho, et al., 2017 [48] | ||

| Glaucoma | Mobin, et al., *[47] | ||||

| stimulating | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Commiphora myrrha (Nees) | Myrrh | Pain, inflammation and throat infection | Mohamed, et al., [49] | ||

| Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J.B. Gillett | Umburana | Anti-inflammatory | Dantas-Medeiros, et al., [50] | Dantas-Medeiros, et al., [50] | |

| Celasteraceae | |||||

| Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. ex Reissek | Espinheira-santa | Gastritis, stomach pain and ulcers | Jorge, et al., [51]/Tabach, et al., [52] | ||

| Gynecological diseases | Colacite, et al., [53]/Oliveira, et al., *[54] | ||||

| Costaceae | |||||

| Costus spicatus Swartz | Cana-de-macaco | Urinary infections | Uliana, et al., [55] | Moreno, et al., *[56] | |

| Crassulaceae | |||||

| Kalanchoe brasiliensis Cambess and Klanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. | Miracle leaf | Body swelling, stomach pain, intestinal problems, eye irritation, inflammation, excess ear wax and hemorrhoid treatment | Araújo, et al., *[57]/Araújo, et al., *[58] | ||

| Excess ear wax | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Euphorbiaceae | |||||

| Euphorbia tirucalli (L.) | Pencil cactus | Wart treatment | Betancur-Galvis, et al., *[59]/Abdel-Aty, et al., *[60] | ||

| Fabaceae | |||||

| Stryphnoden-dron adstringens (Mart.) | Barbatimão | Gynecological diseases | Freitas, et al., [61]/Kaplum, et al., [62] | ||

| Psychiatric problems and hallucinations | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Clitoria ternatea (L.) | ASIAN pigeonwings | Diabetes and insulin resistance | Daisy, et.al., [63] | ||

| Humiriaceae | |||||

| Endopleura uchi (Huber) Cuatrec. | Uxi-amarelo | Fibroid treatment, antitumor | Bento, et al., [64]/Bento, et al., [65] | ||

| Female infertility treatment | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Lamiaceae | |||||

| Rosmarinus officinalis (L.) | Rosemary | Mood stabilizer | Machado, et al., [66]/Machado, et al., [67] | ||

| Lavandula sp. (L.) | Lavender | Calming, sedative | Gilani, et al., [68] | Gilani, et al., [68] | |

| Melissa oficinalis (L.) | Lemon balm | Calming, sedative | Soulimani, et al., [69] | Kennedy, et al., [70] | |

| Mentha x piperita (L.) | Peppermint | Gas, intestinal ache, stomachache | Kannah, et al., [71] | ||

| Cough and flu-like symptoms | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Mentha spicata (L.) | Common mint | Gas, intestinal ache, stomach diseases | Mahboudi, et al., [72] | ||

| Cough and flu-like symptoms | Karaka, et al., *[73]/Hashmi, et al., *[74] | Rodrigues, et al., [75] | |||

| Ocium basilicum (L.) | Basil | inflammations | Selvakkumar, et al., [76] | ||

| Physical and mental exhaustion | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Ocium gratissimum (L.) | African basil | Sinusitis and nasal congestion | Prabhu, et al., *[77] | ||

| Plectranthus barbatus (Andrews) | Tapete-de-Oxalá | Stomach and digestive problems | Alasbahi, et al., [78,79] | ||

| Lauraceae | |||||

| Laurus nobilis (L.) | Bay leaf | Arterial hypertension | De Marino, et al., [80] | Taroq, et al., [81] | |

| Digestive problems | Qnais, et al., [82] | ||||

| Melastomataceae | |||||

| Miconia albicans (Sw.) DC. | Canela-de-velho | Rheumatic ache | Lima, et al., [83]/Corrêa, et al., [84] | ||

| Menispermaceae | |||||

| Cissampelos fasciculata Benth | Erva-mãe-boa | Gynecological diseases | Galinis, et al., *[85]/Souza, et al., *[86] | ||

| Monimiaceae | |||||

| Peumus boldus Molina | Boldo | Digestive problems | Lagos, et al., [87] | ||

| Myristiaceae | |||||

| Myristica fragrans Houtt | Nutmeg tree | Arterial hypertension | Nugraha, et al., [88] | ||

| Myrthaceae | |||||

| Psidium cattleyanum Sabine | Strawberry guava | Intestinal colic and diarrhea | Rahman, et al., [89] | Rahman, et al., [89] | |

| Eucalyptus sp. | Eucalypt | Breathing diseases | Soleimani, et al., [90] | ||

| Eugenia uniflora (L.) | Pitanga | Colds and flu, various respiratory tract infections | Auricchio, et al., *[91]/Soares, et al.,*[92] | ||

| Immunostimulant | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Phyllantaceae | |||||

| Phyllanthus sp. | Stonebraker | Kidney stones | Micali, et al., [93] | ||

| Phytolaccaceae | |||||

| Petiveria alliacea (L.) | Guinea | Anti-inflammatory and analgesic | Lopes-Martins, et al., [94]/Rosa, et al., 2018 [95] | ||

| Piperaceae | |||||

| Piper umbellatum (L.) | Capeba | Muscle aches | Iwamoto, et al., [96]/Arunachalam, et al., [97] | ||

| Peperomia pellucia Kunth | Pepper elder | Eye irritation, gynecological diseases | Oloyed, et al., *[98] | Arrigoni-Blank, et al., *[99] | |

| Poaceae | |||||

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf. | Lemongrass | Stomach problems, flu, cough, breathing problems and general flu-like symptoms | Boukhatem, et al., *[100]/Aiemsaard, et al., *[101] | Boukhatem, et al., *[100] | |

| Insomnia | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Cymbopogon nardus (L.) Rendle | Citronella | Repellent against mosquitoes | Solomon, et al., [102] | ||

| Punicaceae | |||||

| Punica granatum (L.) | Pomegranate | Throat infections, tonsillitis, canker sores | Schubert, et al., *[103]/Al Zoreky, et al.,*[104] | ||

| loss of hear | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Rosaceae | |||||

| Rosa alba (L.) | White rose | Anti-inflammatory | --- | --- | --- |

| calming | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Rubiaceae | |||||

| Uncaria tomentosa (Willd. ex Schult.) DC. | Unha-de-gato | Antibiotic | Ccahuana-Vasquez, et al., [105] | ||

| antitumor | Rizzi, et al., [106] | Dreifuss, et al., [107] | |||

| Rutaceae | |||||

| Ruta graveolens (L.) | Common rue | Inflammatory and colic | Raghav, et al., [108] | Park, et al., [109] | |

| Citrus limon (L.) Burm F. | Sicilian lemon | Immunomodulator | Baba, et al., [110]/Rahman, et al., [111] | ||

| Stimulating | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Citrus × sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Orange tree | Calming | Gusmán-Gutierrez, et al., [112] | ||

| Nausea and stomacaches | Handan, et al., *[113] | Gargano, et al., [114]/Kwangjai, et al., [115] | |||

| Citrus reticulata Blanco | Tangerine tree | Anxiety and insomnia | |||

| Sonalaceae | |||||

| Solanum americanum Miller | American black nightshade | Healing | Valya, et al., *[116] | Joshi, et al., *[117] | |

| Cestrum sp. | Lady of the night | Anti-inflammatory | Begum, et al., [118] | ||

| Zingiberaceae | |||||

| Zingiber officinale (Roscoe) | Ginger | Estimulating | --- | --- | --- |

| Immunomodulator | Zakaria-Rangkat, et al., [119] | Zidan, et al., [120]/Ahmadifar, et al., [121] | |||

| Alpinia zerumbet (Pers.) | Shell ginger | Insomnia, anxiety | |||

| Cardiac diseases | Murakamia, et al., [122]/Bastos, et al., [123]/Paulino, et al., | ||||

| Caption: *=Study with demonstration of pharmacological activity correlated to the cited therapeutic indication, but not with exactly the same indication description (example: anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antimicrobial activity for “throat problems”)/---=No type of study found for the reported indication or biological activity that corroborates the indication. | |||||

Table 2: Correlation between medicinal plants, therapeutic indications and scientific studies with positive evidence for the reported indication.

The data indicate a high correlation between the traditional knowledge of the members of the surveyed Terreiro communities and the results of pharmacological assays from in vitro, in vivo/ex vivo and clinical studies, however, it is important to emphasize the scarce clinical studies found in the literature, as well as, in most cases, the low number of in vivo studies, making more in vivo and clinical studies extremely necessary to establish the efficacy and safety of use in the reported indications. Furthermore, it is important that pharmacological assays be developed with isolated substances, for a better understanding of the mechanisms of action of the active principles of these medicinal plants.

Analysis between the use of medicinal plants in different administrative regions and between different religious strands

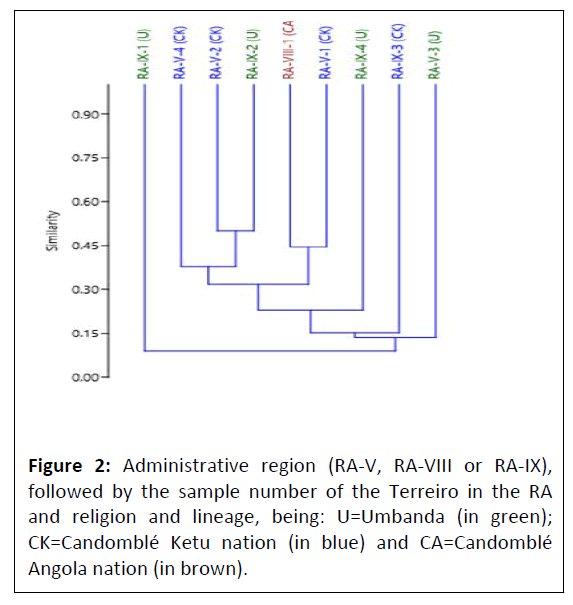

In order to verify whether there is formation of groups with greater similarity to each other, either due to the phytophysiognomies of the Atlantic Forest corresponding to the place where the Terreiros are installed or due to the religion and line/nation of the participating Terreiros, a denogram of similarity was made, from the matrix of presence and absence of citation of each species by participating terreiro (Figure 2). Denogram with classic hierarchical cluster analysis (cluster analysis) for the mentioned medicinal plants, using the UPGMA algorithm and Bray-Curtis similarity index, through the PAST® statistical software.

The hierarchical cluster analysis (Figure 2) did not demonstrate the formation of specific groups by degree of similarity between the mentioned medicinal plant species, neither in relation to the plant phytophysiognomies of the Terreiros' location, nor in relation to the religion and line/nation of the Terreiros participants. This data may indicate that the use of medicinal plants by the Terreiro people went beyond the differences in the vegetation of the place where the Terreiros are inserted, since most of these plants are either cultivated or bought at fairs, as well as surpassed religion and lineage/nation, through the movement of exchange and syncretism of traditional knowledge of each line/nation, as happened with cultural and religious syncretism.

A multivariate ordering analysis was also carried out using the non-metric MDS method (Figure 3), in order to obtain a new analysis on the possible formation of groups with greater similarity due to the phytophysiognomies of the native forest where the Terreiros are located. Multivariate ordering analysis using the non-metric MDS method with the Bray-Curtis distance index, calculated using the PAST® statistical software for the medicinal plants mentioned by Terreiro.

The multivariate ordering analysis by the non-metric MDS method, did not demonstrate the formation of specific groups by degree of similarity between the cited species, nor in relation to the plant physiognomies of the location of the yards. These data reinforce the theory that the use of medicinal plants by the people of the Terreiro surpassed the differences in the vegetation of the place where the Terreiros are inserted, not being the phytophysiognomy of the native forest where the Terreiro is located a preponderant factor for the use of a certain medicinal plant.

Use of Unconventional Food Plants (UFPs)

After explaining to the interviewees, the concept of UFPs as plants, or parts thereof that, despite being edible, are not usually used by the local population as food, we asked them to list which plants they considered UFPs and used in food, whether ritualistic or every day. All citations were considered, as what is not considered UFPs in a given region may be considered in another [7]. Thus, it was not evaluated whether, technically, a mentioned plant would in fact be UFPs in Salvador/BA, but the perception of the interviewees of the plant in this category. We highlight, for example, the mention of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) which was considered UFPs by an interviewee who considered the root medicinal and unusual in cooking, despite being a common plant in oriental cuisine.

Eighteen species considered UFPs by the interviewees were cited (Table 3), the most representative being: Talinum triangulare Jacq. Willd (língua-de-vaca), Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng (Mexican mint), Xanthosoma sagittifolium L.(taioba), Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. (mustard), Dioscorea spp.(yam) and Pereskia aculeata Miller (ora-pronobis). Most of these species have a good supply of mineral salts, in addition to antioxidant action.

| Botanical classification | Commom name | Place of obtening | Used part | Preparation mode | Items added in preparation | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annonaceae | ||||||

| Annona squamosa (L.) | Sweetsops | Fair | Fruit | In natura | Salad to taste | 1 |

| Apiaceae | ||||||

| Coriandrum sativum (L.) | Coriander | Marketplace | Leaves | Cooked in beans or in natura | Beans and salad | 1 |

| Araceae | ||||||

| Colocasia sp. e Xanthosoma sp. | Cará (yam) | Fair | Roots | Boiled | Seasoning to taste | 1 |

| Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) | Taioba | Fair | Leaves | Boiled | Shrimp, onion and palm oil | 3 |

| Asteraceae | ||||||

| Acmella oleracea (L.) R.K.Jansen | Jambú (Oripepê) | Fair | Whole herb | Boiled | Seasoning to taste | 1 |

| Brassicaceae | ||||||

| Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. | Mostard | Fair | Leaves | Fry in olive oil and make farofa | Farinha e camarão seco | 2 |

| Cactaceae | ||||||

| Pereskia aculeata Miller | Ora-pro-nóbis | Fair | Leaves | In natura ou refogado | Seasoning and salad to taste | 2 |

| Dioscoreaceae | ||||||

| Dioscorea sp. | Inhame (yam) | Fair | Roots | Boiled or mush | Shrimp, onion and oliva oil | 2 |

| Euphorbiaceae | ||||||

| Manihot esculenta (Crantz) | Manioc | Fair | Leaves | Boiled for 7 days | Seasoning to taste | 1 |

| Fabaceae | ||||||

| Clitoria ternatea (L.) | Asian pigeonwings | Backyard | Flowers | Macerado em álcool | Food coloring | 1 |

| Bauhinia forficata Link. | Pata-de-vaca | Fair | Leaves | Boiled | Seasoning to taste | 1 |

| Lamiaceae | ||||||

| Rosmarinus officinalis (L.) | Rosimary | Fair | Leaves | Boiled as seasoning | season chicken and pasta | 1 |

| Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng | Mexican mint | Backyard | Leaves | Macerated in the seasoning | Beans and others | 3 |

| Ocimum basilicum (L.) | Basil | Backyard | Leaves | Boiled | Mixed with vegetables | 1 |

| Ocimum gratissimum (L.) | African basil | Backyard | Leaves | Mixed with beans | Beans and others | 1 |

| Portulacaceae | ||||||

| Talinum triangulare Jacq. Willd | Língua-de-vaca (efó) | Fair | Leaves and stalk | Braised or as muqueca | Seasoning to taste | 4 |

| Rutaceae | ||||||

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck | Sicilian lemon | Backyard | Leaves | infusion or juice | Not | 1 |

| Zingiberaceae | ||||||

| Zingiber officinale (Roscoe) | Ginger | Marketplace | Roots | Onion and dried shrimp | Like seasoning | 1 |

Table 3: UFPs cited by respondents.

The use of UFPs was not as abundant as the use of plants for medicinal purposes, which may indicate the loss of part of this knowledge over the generations or the possibility of obtaining it in the urban environment, with increasingly restricted space for cultivation, putting pressure on communities to consume foods that are easy to prepare, known as ultra-processed, as well as obtaining them at fairs, markets and hypermarkets. Some plants, such as the quioiô (Ocimum gra issimum L.) were mentioned for both medicinal and food purposes, reinforcing the holistic and integralist view of the Terreiro people, where nutrition and therapy are closely correlated, in addition to the spiritual aspect of their knowledge ancestors.

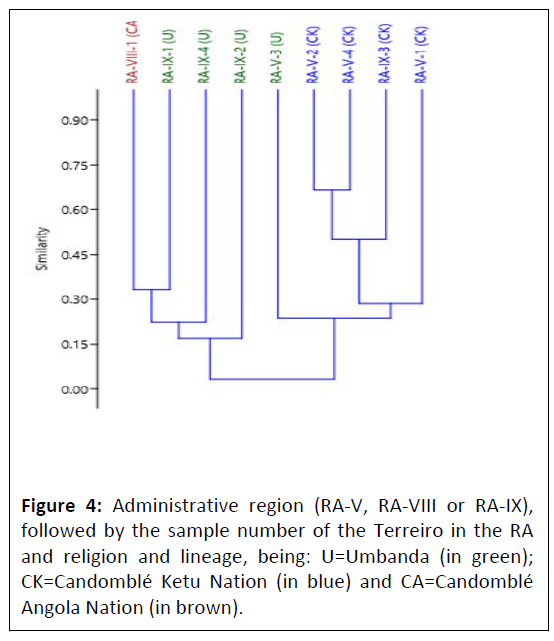

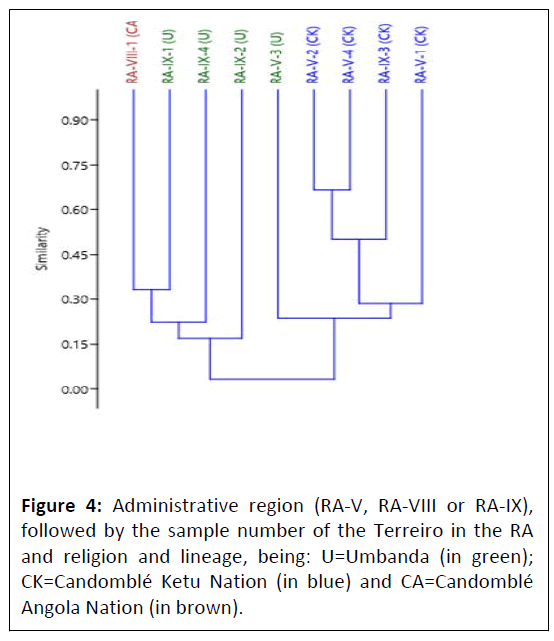

In order to verify whether there is formation of groups with greater similarity to each other, either due to the Atlantic Forest phytophysiognomies corresponding to the place where the Terreiros are installed or due to the religion and line/nation of the participating Terreiros, a denogram of similarity was made, the from the matrix of presence and absence of citation of each species by participating terreiro (Figure 4). Denogram with classic hierarchical cluster analysis (cluster analysis) for the mentioned UFPs, using the UPGMA algorithm and Bray-Curtis similarity index, through the PAST® statistical software.

The hierarchical cluster analysis for the UFPs (Figure 4) demonstrated the formation of groups by degree of similarity between the cited species in relation to the religion and line/ nation of the participating Terreiros and in relation to the administrative regions in which they are inserted, being possible to verify that the Candomblé temples of the Ketu Nation have a greater degree of similarity between themselves, when compared with the Umbanda temples.

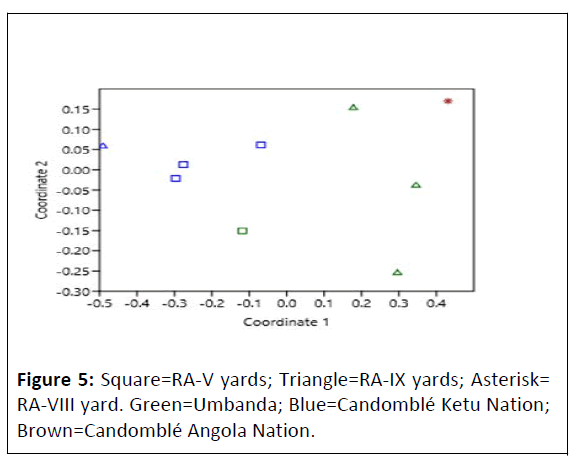

A multivariate ordering analysis was also carried out using the non-metric MDS method (Figure 5), in order to obtain a new analysis on the possible formation of groups with greater similarity due to the phytophysiognomies of the native forest where the Terreiros are located. Multivariate ordering analysis using the non-metric MDS method with the Bray-Curtis distance index, calculated using the PAST® statistical software for the UFPs cited by Terreiro.

The multivariate analysis of ordering by the non-metric MDS method (Figure 5) demonstrated the formation of specific groups by degree of similarity between the cited species, both in relation to administrative regions, religion and nation/line. These data suggest that the consumption of UFPs by the interviewees is more similar between Terreiros of the same line and between Terreiros located in the same region.

Conclusion

The results demonstrate an important use of medicinal plants by the African matrix communities of Salvador researched, as well as an alignment between the pharmacological actions of traditional knowledge with the in vitro, in vivo, ex vivo and clinical pharmacological tests surveyed, demonstrating the importance the preservation of such knowledge and new advances in ethno-directed research. The scarcity of bibliographic references regarding as clinical trials demonstrates that significant advances need to be made in relation to these two aspects, as well as the realization of a greater amount of in vivo research. In addition, the acquisition of plants at fairs was as high as the cultivation for personal use, probably due to the reduction in the size of Terreiros in the urban area, which makes it impossible to plant their own and raises concerns about the correct botanical identification of the acquired plants, as well as hygienic-sanitary conditions, such as the possible presence of contaminants such as heavy metals, insecticides, pathogenic microorganisms, among others.

The use of UFPs was not as expressive as the use of medicinal plants, which may indicate the loss of such knowledge over the generations or the impossibility of access to them by the communities, pressing them to consume easily obtainable foods at fairs and markets. This fact may also be associated with the loss of physical space in urban Terreiros, which are increasingly reduced and unable to maintain the production of their vegetable items for consumption, as previously occurred in the “roças” (farms) present in the Terreiros in the recent past. Perhaps the growing movement to create urban community gardens can boost the rescue of their use, as well as work as a safe source of fresh medicinal plants for the local population.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful for State University of Bahia (UNEB), for Herbarium Alexandre Leal Costa of the Federal University of Bahia (ALCB–UFBA) “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (CAPES)”.

References

- Barbosa WLR, Nascimento MS, Pinto LN, Maia FLC, Souza AJA, et al. (2012) Selecting medicinal plants for development of phytomedicine and use in primary health care. Bioact Com Phytomed 5: 10-15.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Newman DJ, Gragg GM (2007) Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod 70: 461-477.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Costa LO, Pereira GMCL, Rocha JC, Araujo JF, Oliveira LMSR, et al. (2021) Social cartography of Terreiro and traditional peoples' agriculture: An interdisciplinary dialogue for agroecological transition. Int Jou Adv Eng Res Sci 8: 221-232.

[Crossref]

- Pagnocca TS, Zank S, Hanasaki N (2020) The plants have axe: Investigating the use of plants in Afro-Brazilian religions of Santa Catarina Island. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 16: 20

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Brasil. Ministério dos Direitos Humanos. Secretaria Nacional de Políticas de Promoção da Igualdade Racial (2018) Comunidades Tradicionais de Matriz Africana e Povos de Terreiro: Segurança Alimentar, nutricional e Inclusão produtiva. Elaboração de Taís Diniz Garone–Documento eletrônico–Brasília: Ministério dos Direitos Humanos.

- Paz CE, Lemos ICS, Monteiro AB, Delmondes GA, Fernandes GP, et al. (2015) Medicinal plants in Candomblé as an element of cultural resistance and health care. Cuban Magazine of Medicinal Plants 20: 25-37

- Kinupp VF, Lorenzi H (2014) Plantas Alimentícias Não Convencionais (PANC) no Brasil: Guia de identificação, aspectos nutricionais e receitas ilustradas.

- Collins JF (2016) Brazil’s black mecca: Race, justice and entanglements of tradition in Bahia. Lat Amer Res Rev 51: 266-280.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C (2007) Black rome and the chocolate city: The race of place. Callaloo 30: 847-861.

- Camargo MTLA (2014) As plantas medicinais E O Sagrado: A etnofarmacobotânica em uma revisão historiográfica da medicina popular no Brasil. (1st ed) São Paulo. Ícone: 280p.

- Arruda DA, Souz BS, Santos VG, Lima LAA, Santos VG, et al. (2019) Uso de plantas medicinais na Umbanda e Candomblé em associação cultural no município de Puxinanã, Paraíba. Revista Verde 14: 692-696

- Benite AMC, Faustino GAA, Silva JP, Benite CRM (2019) Dai-me Ago (licenca) para falar de saberes tradicionais de matriz africana no ensino de Quimica. Quim Nova 42: 570-579.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Saraceni R (2005) General treatise on Umbanda: Simplified compendium of Umbanda theology, the religion of the mysteries of God; "the interpretive keys. Editora Madras, Sao Paulo.

- Cumino A (2015) Umbanda não é macumba: Umbanda é religião e tem fundamento. (2nd ed), São Paulo: Editora Madras.

- Santos CES (2009) Evaluation of urban expansion against forest remnants located in the administrative regions of Itapuã (RA-X) and Pau da Lima (RA–XIII), Salvador–Bahia.

- Pigozzo CM, Macedo TS, Fernandes LL, Silva DF, Varjão AS, et al. (2007) Comparação florística entre um fragmento de Mata Atlântica e ambientes associados (restinga e manguezal) Na Cidade de Salvador, Bahia. Candomba-Revista Virtual 3: 138-148.

- Martins GA, Lintz A (2000) Guia para elaboração de monografias e trabalhos de conclusão de curso. São Paulo, Atlas. 108 p.

- Mori SA, Berkov AC (2011) Tropical plant collecting. Tecc Editora: p332.

- do Brasil F (2020) Jardim Botanico do Rio de Janeiro.

- Braga AP, de Sousa FI, da Silva Junior GB, Nations MK, Barros ARC, et al. (2018) Perception of candomble practitioners about herbal medicine and health promotion in Ceara, Brazil. J Relig Health 57: 1258-1275.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Silva ASL, de Carvalho MLS, de Jesus BCM (2022) Ethnopharmacological studies in 21st century Brazil: A systematic review. Res Soc Dev 2022: e48211225956.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Bennet BC, Prance GT (2000) Introduced plants in the indigenous pharmacopoeia of Northern South America. Economic Botany 54: 90-102.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Zakay-Rones Z, Varsano N, Zlotnik M, Manor O, Regev L, et al. (1995) Inhibition of several strains of influenza virus in vitro and reduction of symptoms by an elderberry extract (Sambucus nigra L.) during an outbreak of influenza B Panama. J Altern Complement Med 1: 361-369.

- Mahboudi M (2021) Sambucus nigra (black elder) as aternative treatment for cold and flu. Adv Tradit Med (ADTM) 21: 405-414.

- Rouf R, Uddin SJ, Sarker DK, Islam MT, Ali ES, et al. (2020) Antiviral potential of garlic (Allium sativum) and its organosulfur compounds: A systematic update of pre-clinical and clinical data. Trends Food Sci Technol 104: 219-234.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Lissiman E, Bhasale AL, Cohen M (2014) Garlic for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11: CD006206.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Naseri MKG, Aarabian M, Badavi M, Ahangarpour A (2008) Vasorelaxant and hypotensive effects of Allium cepa peel hydroalcoholic extract in rat. Pak J Biol Sci 11: 1569-1575.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Jettanacheawchankit S, Sasithanasate S, Sangvanich P, Banlunara W, Thunyakitpisal P, et al. (2009) Acemannan stimulates gingival fibroblast proliferation; expressions of keratinocyte growth factor-1, vascular endothelial growth factor, and type I collagen; and wound healing. J Pharmacol Sci 109: 525-31.

- Langmead L, Feakins RM, Goldthorpe S, Holt H, Tsironi E, et al. (2004) Randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial of oral aloe vera gel for active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 19: 739-747.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Monzote L, Montalvo AM, Scull R, Miranda M, Abreu J (2007) Activity, toxicity and analysis of resistance of essential oil from Chenopodium ambrosioides after intraperitoneal, oral and intralesional administration in BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania amazonensis: A preliminary study. Biomed Pharmacother 61: 148-153.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Trivellatograssi L, Malheiros A, Meyer-Silva C, Buss ZS, Monguilhott ED, et al. (2015) In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Costus spicatus swartz used in folk medicine for urinary tract infection in Brazil. Lat Am J Pharm 34: 766-772.

- Cavalher-Machado SC, Rosas EC, Brito FA, Heringe AP, Oliveira RR, et al. (2008) The anti-allergic activity of the acetate fraction of Schinus terebinthifolius leaves in IgE induced mice paw edema and pleurisy. Int Immunopharmacol 8: 1552–1560.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Lucena PLH, Ribas Filho JM, Mazza M, Czeczko NG, Dietz UA, et al. (2006) Avaliação da ação da Aroeira (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi) na cicatrização de feridas cirúrgicas em bexigas de ratos. Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira 21: 8-15.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Amorim MMR, Santos LC (2003) Tratamento da vaginose bacteriana com gel vaginal de Aroeira (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi): Ensaio clínico randomizado. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 25: 95-102.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Sokpe A, Mensah MLK, Koffuor GA, Thomford KP, Arthur R, et al. (2020) Hypotensive and antihypertensive properties and safety for use of Annona muricata and Persea americana and their combination products. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020: 8833828.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Oridupa OA, Oyagbemi AA, Adejumobi O, Falade FB, Obisesan AB, et al. (2021) Compensatory depression of arterial pressure and reversal of ECG abnormalities by Annona muricata and Curcuma longa in hypertensive wistar rats. J Complement Integr Med 19: 375-382.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Kumar D, Bhat ZA (2012) Anti-anxiety activity of methanolic extracts of different parts of Angelica archangelica linn. J Tradit Complement Med 2: 235-241.

- Kumar D, Bhat ZA, Kumar V, Shah MY (2013) Coumarins from Angelica archangelica Linn. and their effects on anxiety-like behavior. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 40:180-186.

- Al-Mofleh IA, Alhalder AA, Mossa JS, Alsoohalbani MO, Rafatullah S (2007) Aqueous suspension of anise “Pimpinella anisum” protects rats against chemically induced gastric ulcers. World J Gastroenterol 13: 1112-1118.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Ghoshegir SA, Mazaheri M, Ghannadi A, Feizi A, Babaeian M, et al. (2015) Pimpinella anisum in the treatment of functional dyspepsia: A double-blind, randomized clinical trial. J Res Med Sci 20: 13-21.

- Silva JB, Mendes RF, Tomasco V, Pinto NCC, Oliveira LG, et al. (2017) New aspects on the hepatoprotective potential associated with the antioxidant, hypocholesterolemic and anti-inflammatory activities of Vernonia condensata baker. J Ethnopharmacol 198:399-406.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Boeing T, Silva LM, Somensi LB, Cury BJ, Costa APM, et al. (2016) Antiulcer mechanisms of Vernonia condensata baker: A medicinal plant used in the treatment of gastritis and gastric ulcer. J Ethnopharmacol 184: 196-207.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Lyss G, Schmidt TJ, Merfort I, Pahl HL (1997) Helenalin, an anti-inflammatory sesquiterpene lactonefrom arnica, selectively inhibits transcription factor NF-κΒ. Biol Chem 378: 951-961.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Widrig R, Suter A, Saller R, Melzer J (2007) Choosing between NSAID and arnica for topical treatment of hand osteoarthritis in a randomised, double-blind study. Rheumatol Int 27: 585-591.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Viola H, Wasowski C, Stein ML, Wolfman C, Silveira R (1995) Apigenin, a component of Matricaria recutita flowers, is a central benzodiazepine receptors-ligand with anxiolytic effects. Planta Med 61: 213-216.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Bozorgmehr B, Mojab F, Faizi M (2012) Evaluation of sedative-hypnotic effect of ethanolic extract of five medicinal plants; Nepeta menthoides, Matricaria chamomilla, Asperugo procumbens, Lippia citriodora and Withania somnifera. Res Pharmac Sci 7: 5-10.

- Mobin M, Lima SG, Almeida LTG, Filho JCS, Rocha MS, et al. (2017) Gas chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry analysis and vasorelaxant effect of essential oil from Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) March. Biomed Res Int 2017: 1928171.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Carvalho KMMB, Melo TS, Melo KM, Quindere ALG, de Oliveira FTB, et al. (2017) Amyrins from Protium heptaphyllum reduce high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice via modulation of enzymatic, hormonal and inflammatory responses. Planta Med 83: 285-291.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Mohamed AA, Ali SI, El-Baz FK, Hegazy AK, Kord MA (2014) Chemical composition of essential oil and in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of crude extracts of Commiphora myrrha resin. Ind Crops Prod 57: 10-16.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Medeiros R, Furtado AA, Zanatta AC, Torres-Rego M, Lourenco EMG, et al. (2021) Mass spectrometry characterization of Commiphora leptophloeos leaf extract and preclinical evaluation of toxicity and anti-inflammatory potential effect. Jour Ethnopharm 264: p113229.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Jorge RM, Leite JPV, Oliveira AB, Tagliati CA (2004) Evaluation of antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antiulcerogenic activities of Maytenus ilicifolia. J Ethnopharmacol 94: 93-100.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Tabach R, Duarte-Almeida JM, Carlini EA (2017) Pharmacological and toxicological study of Maytenus ilicifolia leaf extract. Part I-preclinical studies. Phytother Res 31: 915-920.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Colacite J (2015) Triagem fitoquimica, analise antimicrobiana e citotoxica e dos extratos das plantas: Schinus terebinthifolia, Maytenus ilicifolia reissek, Tabebuia avellanedae, Anadenanthera colubrina (vell.) brenan. Rev Saude e Pesqu 8: 509-516.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira RM (2016) Phytochemical analysis and evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Maytenus ilicifolia (Mart. ex Reissek).

- Uliana MP, Silva AG, Fronza M, Scherer R (2015) In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of costus spicatus swartz used in folk medicine for urinary tract infection in brazil. Lat Am J Pharm 34: 766-772.

- Moreno KGT, Gasparotto JA, Santos C, Palozi RACP, Guarnier LP, et al. (2021) Nephroprotective and antilithiatic activities of Costus spicatus (Jacq.) Sw: Ethnopharmacological investigation of a species from the Dourados region, Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol 266: 113409.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Araujo ERD (2017) Kalanchoe brasiliensis Cambess e Kalanchoe Pinnata (Lamarck) persoon: Caracterizacao química, avaliacao gastroprotetora E anti-inflamatoria topica. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

- Araujo ERD, Felix-Silva J, Xavier-Santos JB, Fernandes JM, Guerra GCB, et al. (2019) Local anti-inflammatory activity: Topical formulation containing kalanchoe brasiliensis and Kalanchoe pinnata leaf aqueous extract. Biomed Pharmacother 113: p108721.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Betancur-Galvis LA, Morales GE, Forero JE, Roldan J (2002) Cytotoxic and antiviral activities of colombian medicinal plant extracts of the Euphorbia genus. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 97: 541-546.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Abdel-Aty AM, Hamed MB, Salama WH, Ali MM, Fahmy AS, et al. (2019) Ficus carica, Ficus sycomorus and Euphorbia tirucalli latex extracts: Phytochemical screening, antioxidant and cytotoxic properties. Biocat Agri Biotech 20: p101199.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Freitas ALD, Kaplum V, Rossi DCP, Silva LBR, Melhem MSC, et al. (2018) Proanthocyanidin polymeric tannins from stryphnodendron adstringens are effective against Candida spp. isolates and for vaginal candidiasis treatment. J Ethnopharmacol 216: 184-190.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Kaplum V (2018) Fracao Enriquecida em proantocianidinas de Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) coville: Atividade em linhagens celulares de cancer cervical, tumor solido de Ehrlich e ensaio clinico fase I. Doctoral Dissertation, State University of Maringá, Brazil.

- Daisy P, Rajathi M (2009) Hypoglycemic effects of Clitoria ternatea linn. (fabaceae) in alloxan-induced diabetes in rats. Trop Jour Pharm Res 8: 393-398.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Bento JF (2013) Caracterização de polissacarídeos e metabólitos secundários da casca de Endopleura uchi (Huber) Cuatrec: avaliação dos efeitos do decocto e das frações polissacarídicas em células HeLa e macrófagos. Thesis (Postgraduate Degree in Biochemistry)-Federal University of Paraná, Brazil.

- Bento JF, Noleto GR, Petkowicz CLO (2014) Isolation of an arabinogalactan from Endopleura uchi bark decoction and its effect on HeLa cells. Carbohydr Polym 101: 871-877.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Machado DG, Bettio LEB, Cunha MP, Capra JC, Dalmarco JB, et al. (2009) Antidepressant-like effect of the extract of Rosmarinus officinalis in mice: Involvement of the monoaminergic system. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33: 642-650.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Machado DG, Cunha MP, Neis VB, Balen GO, Colla AR, et al. (2012) Rosmarinus officinalis L. hydroalcoholic extract, similar to fluoxetine, reverses depressive-like behavior without altering learning deficit in olfactory bulbectomized mice. J Ethnopharmacol 143:158-169.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Gilani AH, Aziz N, Khan MA, Shaheen F, Jabeen Q, et al. (2000) Ethnopharmacological evaluation of the anticonvulsant, sedative and antispasmodic activities of lavandula stoechas L. J Ethnopharmacol 71: 161-167.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Soulimani R, Fleurentin J, Mortier F, Misslin R, Derrieu G, et al. (1991) Neurotropic action of the hydroalcoholic extract of Melissa officinalis in the mouse. Planta Med 57: 105-109.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Kennedy DO, Little W, Scholey AB (2004) Attenuation of laboratory-induced stress in humans after acute administration of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm). Psychosom Med 66: 607-613.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Kannah RMD, Macdonald JKMA, Levesque BGMD (2014) Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol 48: 505-512.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Mahboudi M (2021) Mentha spicata L. essential oil, phytochemistry and its effectiveness in flatulence. J Tradit Complement Med 11: 75-81.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Karaka N, Demirci B, Demirci F (2018) Evaluation of Lavandula stoechas L. subsp. Stoechas L., Mentha spicata L. subsp. Spicata L. essential oils and their main components against sinusitis pathogens. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci 73: 1-10.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Hashmi Z, Sarkar D, Mishra S, Mehra V (2022) An in-vitro assessment of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-hyperglycemic activities of traditional edible plants-Murraya koenigii, Mentha spicata and Coriandrum sativum. Jour Biomed Therap Sci 9: 1-10.

- Rodrigues LB, Martins AOBPB, Ribeiro-Filho J, Cesário FRAS, Castro FFE, et al. (2017) Anti-inflammatory activity of the essential oil obtained from Ocimum basilicum complexed with β-Cyclodextrin (β-CD) in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 109: 836-846.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Selvakkumar C, Gayathri B, Vinaykumar KS, Lakshmi BS, Balakrishman A (2007) Potential anti-inflammatory properties of crude alcoholic extract of Ocimum basilicum L. in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Health Sci 53: 500-505.

- Prabhu KS, Lobo R, Shirwaikar AA, Shirwaikar A (2009) Ocimum gratissimum: A review of its chemical, pharmacological and ethnomedicinal Properties. J Complement 1: 1-15.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Alasbahi RH, Melzig MF (2010) Plectranthus barbatus: A review of phytochemistry, ethnobotanical uses and pharmacology-Part 1. Planta Med 76: 653-661.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Alasbahi RH, Melzig MF (2010) Plectranthus barbatus: A review of phytochemistry, ethnobotanical uses and pharmacology-Part 2. Planta Med 76: 753-665.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- De Marino S, Borbone N, Zollo F, Ianaro A, Di Meglio P, et al. (2005) New sesquiterpene lactones from Laurus nobilis leaves as inhibitors of nitric oxide production. Planta Med 71: 706-710.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Taroq A, Bakour M, El Atik Y, El Kamari F, Aouam I, et al. (2021) Comparative studies of the effects of Laurus nobilis and Zyzygium aromaticum aqueous extracts on urine volume and renal function in rats. Int J Pharm Sci Res 12: 776-782.

[Crossref]

- Qnais EY, Abdulla FA, Kaddumi EG, Abdalla SS (2012) Antidiarrheal activity of Laurus nobilis L. leaf extract in rats. J Med Food 15: 51-57.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Lima TC, Matos SS, Carvalho TF, Silveira-Filho AJ, Couto LPSM, et al. (2020). Evidence for the involvement of IL-1β and TNF-α in anti-inflammatory effect and antioxidative stress profile of the standardized dried extract from Miconia albicans Sw. (Triana) Leaves (Melastomataceae). J Ethnopharmacol 259: 112908.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Correa JGS, Bianchin M, Lopes AP, Silva E, Ames FQ, et al. (2021) Chemical profile, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of Miconia albicans (sw.) triana (Melastomataceae) fruits extract. J Ethnopharmacol 273: p113979.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Galinis DL, Wiemer DF, Cazin J (1993) Cissampentin: A new bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloid from cissampelos fasciculata. Tetrahedron 49: 1337-1342.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Souza ER, Cruz CC, Almeida MR, Dantas MCSM, Oliveira AMS, et al. (2012) Avaliação da atividade antibacteriana dos óleos voláteis e extratos de plantas da comunidade de Três Lagoas, Amargosa-BA.

- Lagos JFP, Zamorano-Ponce E (2009) Effect of boldo (Peumus boldus Molina) infusion on lipoperoxidation induced by cisplatin in mice liver. Phytother Res 23: 1024-1027.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Nugraha APHS, Widyawaty ED, Hernanto FF, Indrianita V, Kristianto H (2020) Effect of nutmeg and lavander essential oil on blood pressure in the elderly with hypertension. Arch's J Archaeol Egypt 17: 10076-10083.

- Rahman HMA, Saghir KA, Haider MS, Javaid U, Rasool MF (2020) Pharmacological modulation of smooth muscles and platelet aggregation by Psidium cattleyanum. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020: 4291795.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Soleimani G, Shahri ES, Ansari H, Ganjali A, Mollazehi AA (2021) Effectiveness of the Eucalyptus inhalation on the upper respiratory tract infections of 5-15 years old children. The Horizon of Medical Sciences 27: 566-575.

- Auricchio MT, Bugno A, Barros SBM, Elfriede M, Bacchi EM (2007) Atividades antimicrobiana e antioxidante e toxicidade de Eugenia uniflora. Lat Americ Jour Pharm 26: 76-81.

- Soares DJ (2014) Efeitos antioxidante e antiinflamatório da polpa de pitanga roxa (Eugenia uniflora L.) sobre células bucais humanas, aplicando experimentos in vitro e-ex vivo. Doctoral Dissertation, Federal University of Ceará, Brazil.

- Micali S, Sighnolfi MC, Celia A, De Stefani S, Otimo M, et al. (2006) Can Phyllanthus niruri affect the efficacy of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for renal stones? A randomized, prospective, long-term study. J Urol 176: 1020-1022.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Lopes-Martins RAB, Pegoraro DH, Woisky R, Penna SC, Sertie JAA (2002) The anti-Inflammatory and analgesic effects of a crude extract of Petiveria alliacea L. (Phytolaccaceae). Phytomedicine 9: 245-248.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Rosa MPG, Jose MMF (2018) Petiveria alliacea suppresses airway inflammation and allergen-specific Th2 responses in ovalbumin-sensitized murine model of asthma. Chin J Integr Med 24:912-919.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Iwamoto LH, Vandramini-Costa DB, Monteiro PA, Ruiz ALTG, Sousa IMO, et al. (2015) Anticancer and anti-inflammatory activities of a standardized dichloromethane extract from Piper umbellatum L. leaves. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015: 948737.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Arunachalam K, Damazo AS, Macho A, Lima JCDS, Pavan E, et al. (2020) Piper umbellatum L. (piperaceae): Phytochemical profiles of the hydroethanolic leaf extract and intestinal anti-inflammatory mechanisms on 2,4,6 trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid induced ulcerative colitis in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 254: p112707.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Oloyed GK, Onocha PA, Olaniran BB (2011) Phytochemical, toxicity, antimicrobial and antioxidant screening of leaf extracts of Peperomia pellucida from Nigeria. Adv Environ Biol 5: 3700-3709.

- Arrigoni Blank MF, Dmitrieva EG, Franzotti EM, Antoniolli AR, Andrade MR, et al. (2004) Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of Peperomia pellucida (l.) hbk (piperaceae). J Ethnopharmacol 91: 215-218.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Boukhatem MN, Ferhat MA, Kameli A, Saidi F, Kebir HT (2014) Lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil as a potent anti-inflammatory and antigungical drugs. Libyan J Med 9: p25431.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Aiemsaard J, Aiumlamai S, Aromdee C, Taweechaisupapong S, Khunkitti W (2011) The effect of lemongrass oil and its major components on clinical isolate mastitis pathogens and their mechanisms of action on Staphylococcus aureus DMST 4745. Res Vet Sci 91: 31-37.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Solomon B, Gebre-Mariam T, Asres K (2012) Mosquito repellent actions of the essential oils of Cymbopogon citratus, Cymbopogon nardus and Eucalyptus citriodora: Evaluation and formulation studies. J Essent Oil-Bear 15: 766-773.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Schubert S, Lansky E, Neeman I (1999) Antioxidant and eiocsanoid enzyme inhibition properties of pomegranate seed oil and fermented juice flavonoids. J Ethnopharmacol 66: 11-17.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Al Zoreky NS (2009) Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) fruit peels. Int J Food Microbiol 134: 244-448.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Ccahuana-Vasquez RA, Santos SSF, Koga-Ito CY, Jorge AOC (2007) Antimicrobial activity of Uncaria tomentosa against oral human pathogens. Braz Oral Res 21:46-50.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Rizzi R, Re F, Bianchi A, de Feo V, Simone F, et al. (1993) Mutagenic and antimutagenic activities of Uncaria tomentosa and its extracts. J Ethnopharmacol 38: 63-77.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Dreifuss AA, Bastos-Pereira AL, Avila TV, Soley BS, Rivero AJ, et al. (2010) Antitumoral and antioxidant effects of a hydroalcoholic extract of cat's claw (Uncaria tomentosa) (willd. ex roem. & schult) in an in vivo carcinosarcoma model. J Ethnopharmacol 130: 127-133.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Raghav SK, Gupta B, Agrawal C, Goswami K, Das HR (2006) Anti-inflammatory effect of Ruta graveolens L. in murine macrophage cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacoloy 104: 234-239.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Park SH, Sim YB, Kim SM, Lee JK, Lim SS, et al. (2010) Antinociception effect and mechanism of Ruta graveolens L. in mice. J Appl Biol Chem 53: 593-597.

- Baba E, Acar U, Öntaş C, Kesbiç OS, Yılmaz S (2016) Evaluation of citrus limon peels essential oil on growth performance, immune response of Mozambique tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus challenged with Edwardsiella tarda. Aquaculture 465:13-18.

- Rahman ANA, Elhady M, Shalabi S (2019) Efficacy of the dehydrated lemon peels on the immunity, enzymatic antioxidant capacity and growth of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and African catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Aquaculture 505: 92-97.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Gusman-Gutierrez SL, Navarrete A (2009) Pharmacological exploration of the sedative mechanism of hesperidin identified as the active principle of Citrus sinensis flowers. Planta Med 75: 295-301.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Handan DI, Mohamed ME, Abdulla LH, Mohamed SM, El-Shazly AM (2013) Anti-inflammatory, insecticidal and antimicrobial activities and chemical composition of the essential oils of different plant organs from navel orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck var. Malesy) grown in Egypt. Jour Med Plant Res 7: 1204-1215.

- Gargano AC, Costa CARA, Costa M (2008) Essential oils from Citrus latifolia E Citrus reticulata reduce anxiety and prolong ether sleeping time in mice. Tree fores Sci Biotech 2: 121-124.

- Kwangjai J, Cheaha D, Manor R, Sa-Ih N, Samerphob N, et al. (2021)Modification of brain waves and sleep parameters by Citrus reticulata blanco. cv. sai-nam-phueng essential oil. Biomed J 44: 727-738.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Valya G, Ragan A, Raju VS (2011) Screening for in vitro antimicrobial activity of Solanum americanum miller. Journal of Recent Advances in Applied Sciences 26: 43-46.

- Joshi N, Negi P, Joshi DC (2021) Review on responsible mediators and mechanism of action involved in anti-inflammatory action of Solanum americanum. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 10: 2068-2080.

- Begum AS, Goyal M (2007) Research and medicinal potential of the genus cestrum (solanaceae)-A review. Pharmacognosy Reviews 1: 320-332.

- Zakaria-Rangkat F, Nurahman PE, Tejasari T (2003) Antioxidant and immunoenhancement activities of ginger (Zingiber officinale roscoe) extracts and compounds in in vitro and in vivo mouse and human system. J Food Sci Nutr 8: 96-104.

- Zidan DE, Kahilo KA, El-Far AH, Sadek KM (2016) Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and thymol dietary supplementation improve the growth performance, immunity and antioxidant status in broilers. Glob Vet 16: 530-538.

- Ahmadifar E, Sheikhzadeh N, Roshanaei K, Dargahi N, Faggio C (2019) Can dietary ginger (Zingiber officinale) alter biochemical and immunological parameters and gene expression related to growth, immunity and antioxidant system in zebrafish (Danio rerio)?. Aquaculture 507: 301-348.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Murakamia S, Matsuuraa M, Satoua T, Hayashi S, Koikea K (2009) Effects of the essential oil from leaves of Alpinia zerumbet on behavioral alterations in mice. Nat Prod Commun 4: 129-32.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Bastos JL (2017) Investigation of the anti-inflammatory activity of the ethanolic extract of Alpinia zerumbet (Pers.). Federal University of Sergipe, Brazil.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences