ISSN : 2576-3938

Journal of Emergency and Internal Medicine

A Study of 72 Adult Patients with Cardiopulmonary Arrest Due to Food Asphyxia

Kenichi Katabami*

Emergency and Critical Care Center, Hokkaido University Hospital, Japan

- *Corresponding Author:

- Kenichi Katabami

Emergency and Critical Care Center

Hokkaido University Hospital

Kita 15, Nishi 7, Kita-Ku

Sapporo 060-8638, Hokkaido, Japan

Tel: + 81 117 067377

Fax: + 81 117 067378

E-mail: bamiken_007@yahoo.co.jp

Received date: July 04, 2017; Accepted date: July 18, 2017; Published date: July 20, 2017

Citation: Katabami K (2017) A Study of 72 Adult Patients with Cardiopulmonary Arrest Due to Food Asphyxia. J Emerg Intern Med Vol.1 No.1:7.

Abstract

Introduction: Japan has the highest proportion of elderly individuals globally and the incidence of food asphyxia has been steadily increasing. The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients with cardiopulmonary arrest resulting from food asphyxia.

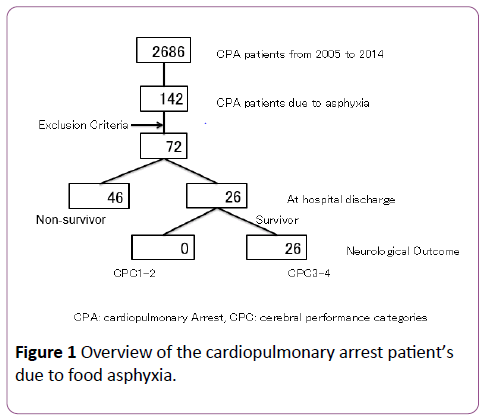

Methods: We retrospectively examined the medical records of 142 patients admitted to our center between January 2005 and December 2014 with cardiopulmonary arrest resulting from food asphyxia. We excluded patients <20 years of age or if relevant clinical data were missing. A total of 72 patients met the overall inclusion criteria.

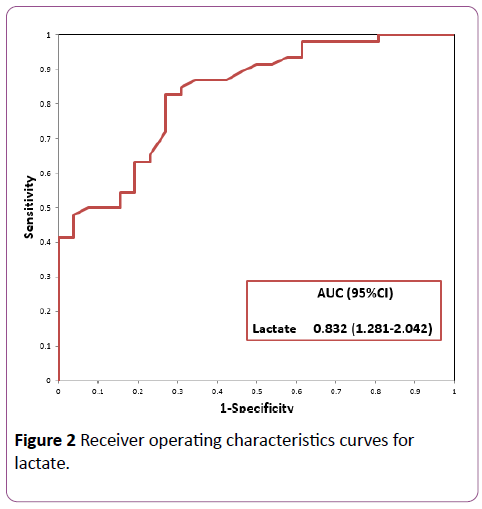

Results: Overall, 26 patients (36%) survived to hospital discharge, but their neurological prognosis was poor. 3 significant variables (pre-hospital medical treatment, time from emergency call to hospital arrival, and lactate level) were selected by stepwise logistic regression and multiple logistic regression was performed with those 3 selected variables. Only blood gas lactate level at the time of admission was an independent predictor of survival to hospital discharge. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses yielded the AUC=0.832 the optimal cut-off value for lactate levels was 10.1 mg/dL (sensitivity, 83% and specificity, 73%) by Youden Index.

Conclusion: These study findings suggest that blood gas lactate level at the time of hospital admission can be a predictor for the outcome of patients with asphyxia.

Keywords

Stroke; Endovascular treatments; Alteplase treatment; Non-sensical speech

Introduction

Japan has the highest proportion of elderly individuals worldwide [1] and the incidence of food asphyxia has been steadily increasing [2]. Asphyxia is a critical condition in the elderly. Adult food asphyxia is often witnessed because it usually occurs during meals; hence, the duration of hypoxia and time of cardiac arrest can be accurately estimated. The Heimlich maneuver is a well-known means of removing foreign bodies from the airway of choking patients. The purpose of this study was to identify prognostic factors related to outcomes of asphyxia patients. A retrospective study was conducted to investigate clinical characteristics, resuscitation profiles, and outcomes of food asphyxiation victims presenting to our institution with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) from January 2005 to December 2014.

Methods

Study design

The study was designed as a single-institution retrospective observational investigation using a database of patients treated at Hokkaido University Hospital from January 2005 to December 2014. This study was approved by our institutional ethics review board.

Participants and study setting

Pre-hospital data on the patients were obtained from Sapporo City Fire Department and were collected in the Utstein style. Patients were excluded from this study if they were younger than 20 years old or if relevant details were missing. Patients were admitted to an intensive care unit after successful resuscitation. Patients with food asphyxiation presenting with OHCA were identified from the database and clinical variables, including age, sex, initial cardiac rhythm, type of food (solid or non-solid), pre-hospital medical treatment, risk factors, time from emergency call to arrival of the emergency medical services, time from emergency call to arrival at the hospital, and blood gas lactate levels at the time of hospital admission were extracted. The primary endpoint was survival to hospital discharge; neurologic outcomes were also evaluated, using cerebral performance categories (CPC). A good outcome was defined as CPC 1 (good recovery) or 2 (moderate disability), and a poor outcome was defined as CPC 3 (severe disability), 4 (vegetative state), or 5 (death).

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics i.e., mean and standard deviations were computed for all continuous variables. Student’s t-test was performed for the comparison of any variables assumed to have normality between survivors and non-survivors, and Mann-Whitney rank sum test for non-normal variables. Categorical variables were compared using Chi square or Fisher’s exact tests. All the statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 12.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and significant level is assumed as 5%. We conducted variable selection by stepwise logistic regression method and performed multiple logistic regression analysis for the detection of prognostic factors toward the outcome. ROC analysis, calculating ROC-AUC and optimal cut-off by Youden Index, were also performed to confirm whether the selected variables hold sufficient discrimination power to the outcome.

Results

During the 10-year period, 142 patients with OHCA following food asphyxiation presented to and were treated at our institution. Of these, 72 patients met the overall inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the 72 patients are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Survivor | Non-survivor | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 79(26) | 80(46) | 0.694 |

| Male sex (n, %) | 10(38.5) | 22(47.8) | 0.441 |

| Initial rhythm | |||

| Asystole/PEA (n) | 12/14 | 33/13 | 0.032 |

| Type of foods | |||

| Solid/Non-solid (n) | 12/14 | 14/32 | 0.185 |

| Pre-hospital doctor’s treatment (n, %) | 24 (92.3) | 28 (60.9) | 0.002 |

| Risk factors (n, %) | 15 (57.7) | 23 (50.0) | 0.529 |

| Time from emergency call | |||

| To hospital arrival (minutes) | 35.1 | 39.0 | 0.082 |

| To EMS arrival (minutes) | 7.15 | 8.04 | 0.139 |

| To EMS arrival (minutes) | 8.12 | 12.77 | 0.000 |

PEA: Pulseless Electrical Activity, EMS: Emergency Medical Service

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients.

Their age ranged from 44 to 100 years, with a mean of 79.9 ± 10.4 years. The male-to-female ratio was 32:40. Twenty-six (36.1%) cases involved solid food masses and 46 (63.9%) nonsolid food masses. Medical risks for swallowing foods were present in 38 (52.8%) cases. Initial rhythms were pulseless electrical activity in 27 (37.5%) patients and asystole in 45 (62.5%). The time from placement of the emergency call to arrival of the emergency medical services and to hospital arrival did not differ significantly between survivors and nonsurvivors. Overall, 26 (36%) patients survived to hospital discharge, but all survivors had poor neurologic outcome scores (CPC 3–4).

Stepwise multiple logistic-regression analysis showed that lactate level (adjusted odds ratio, 1.579; 95% CI, 1.269–2.103; p<0.0001) was associated with in-hospital mortality (Table 2).

We generated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to determine the predictive power of lactate levels for inhospital mortality. The area under the curve (AUC) for the ROC curve of lactate levels was 0.832 (95% CI, 1.281-2.042) (Figure 2). The cutoff value for blood lactate level that maximized the sum of sensitivity and specificity was 10.1 mg/dL. This value yielded a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 73% for predicting in-hospital mortality.

| Variables | Odds ratio | p-value | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-hospital doctor’s treatment | 0.211 | 0.060 | 0.027-1.061 |

| Time from emergency call | |||

| To hospital arrival | 1.089 | 0.057 | 0.998-1.206 |

| Lactate | 1.579 | 0.000 | 1.269-2.103 |

Note: The results of the final step of the analyses are shown. The dependent variables on the first steps: age, sex, initial rhythm, type of foods, pre-hospital doctor’s existence, risk factors, time from emergency call to hospital arrival, time from emergency call to arrival of emergency medical service, and lactate.

Table 2: Stepwise logistic regression analyses for prediction of the outcome (death).

Discussion

Food asphyxiation is increasing as a cause of sudden death among the elderly in Japan. In one study, the annual incidence of sudden death from food asphyxiation was calculated to be 0.66 per 100,000 population [3]. Wick et al. reported that the majority of those who died from food asphyxiation were aged between 71 and 90 years, and most had underlying conditions that adversely affected swallowing, such as dementia [4]. The high rate of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) in patients asphyxiated by food is not surprising because ischemic damage to the heart is less severe in cardiac arrest related to asphyxia than that of primary cardiac etiology [5].

However, most victims have irreversible brain damage after food asphyxiation, which explains the dissociation between the high ROSC rate and very low survival rate. In one study, 68% of those who achieved ROSC were brain dead [6]. This is in sharp contrast with survivors of cardiac OHCA, where approximately 45% to 60% of those with ROSC may survive to hospital discharge [7]. Experimental studies show that the pathophysiological mechanisms of brain injury may differ when caused by cardiac arrest and by asphyxia: In the former, brain oxygen deprivation begins at the time of cardiac arrest. In contrast, asphyxiation causes hypoxia, hypercarbia, and hypotension with incomplete ischemia for several minutes preceding cardiac arrest, resulting in worse histopathological findings [8]. It has been reported that a window of opportunity may exist in survivors of OHCA of cardiac origin, and that the interval between OHCA and ROSC seems to be 20–25 min or less [9]. Although it sounds natural that the shorter the interval the higher the chance of survival for asphyxial OHCA victims, few studies have been conducted on this subject.

Swallow therapy, dietary modification, aggressive oral care, treatment of poor dentition, and treatment with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors have been suggested as ways to reduce the incidence and severity of aspiration pneumonia in the elderly [10]. Considering prevention of food asphyxiation victims, the quality of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is important. In one report, chest compressions by a bystander were found to be the most important action for achieving a good outcome for a foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO) patient who becomes unresponsive or unconscious [11]. Kawahara et al. reported that bystanders tended to focus on removing food material from victim’s mouth with fingers rather than performing standard CPR [12]. Educational seminars on CPR have been conducted widely throughout Japan since the American Heart Association published CPR guidelines in 2000. For patients with FBAO in particular, publication of the guidelines spread awareness of the importance of chest compressions if and when a patient becomes unresponsive or unconscious. Asphyxiation was witnessed in all victims and chest compressions were performed soon after asphyxiation occurred. Most victims, however, sustained irreversible brain damage after food asphyxiation, resulting in a very low survival rate. The patient’s low survival rate of food asphyxiation has been reported by some authors [12].

In some reports, lactate is reported to be a prognostic factor for critical ill patients [13], patients with sepsis [14], and those with OHCA [15]. In our study, lactate levels on admission were identified as the most important prognostic factor for survival to hospital discharge of patients who suffered food asphyxiation. However, the neurologic outcome of survivors from cardiopulmonary arrest caused by food asphyxiation was very poor, even for those with successful ROSC. The CPCs of all survivors were 3–4.

This study has a limitation. It was a retrospective observational study conducted only at our institution. A prospective multicenter study should be conducted to evaluate the prognostic factors for the outcome of patients suffering cardiopulmonary arrest due to food asphyxiation.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that blood gas lactate levels at the time of hospital admission can predict the outcome of patients with asphyxia. However, as with previous reports, we conclude that the neurologic prognosis of patients with cardiopulmonary arrest resulting from food asphyxiation is very poor. So, it is important to prevent food asphyxiation for elderlies. Further, educating to perform standard CPR may be important.

References

- https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2014/zenbun/index.html

- www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/FY2009/dl/accident_3.pdf

- Mittleman RE, Wetli CV (1982) The fatal cafe coronary. Foreign body airway obstruction. JAMA 247: 1285-1288.

- Wick R, Gilbert JD, Byard RW (2006) Café coronary syndrome-fatal choking on food: An autopsy approach. J Clin Forensic Med 13: 135-138.

- McCaul CL, McNamara P, Engelberts D, Slorach C, Horberger LK, et al. (2006) The effect of global hypoxia on myocardial function after successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a laboratory model. Resuscitation 68: 267-275.

- Inamasu J, Miyatake S, Tomioka H, Shirai T, Ishiyama M, et al. (2010) Cardiac arrest due to food asphyxiation in adults: Resuscitation profiles and outcomes. Resuscitation 81: 1082-1086.

- Hypothermia After-Cardiac Arrest Study Group (2002) Mild therapeutic hapothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 346: 549-556.

- Vaagenes P, Safar P, Moossy J, Rao G, Diven W, et al. (1997) Asphyxiation versus ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest in dogs. Differences in cerebral resuscitation effects—A preliminary study. Resuscitation 35: 41-52.

- Oddo M, Ribordy V, Feihl F, Rossetti AO, Schaller MD, et al. (2008) Early predictors of outcome in comatose survivors of ventricular fibrillation and non-ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest treated with hypothermia: A prospective study. Crit Care Med 36: 2296-2301.

- Kikawada M, Iwamoto T, Takasaki M (2005) Aspiration and infection in the elderly: Epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging 22: 115-130.

- Kinoshita K, Azuhata T, Kawano D, Kawahara Y (2015) Relationships between pre-hospital characteristics and outcome in victims of foreign body airway obstruction. Resuscitation 88: 63-67.

- Kawahara Y, Kinoshita K, Murokawa T, Chiba N, KatsushigeT, et al. (2009) Study of fifty cases of foreign body airway obstruction which occurred in front of bystanders. J Jap Assoc Acute Med 20: 755-762.

- Tim C, Jasper VB, Jan B (2009) Blood lactate monitoring in critical ill patients: A systematic health technology assessment. Crit Care Med 37: 2827-2839.

- Bandarn S, Keith RW (2016) Lactic acidosis in sepsis: It’s not all anaerobic. Chest 149: 252-261.

- Tae RL, Mun JK, Won CC, Shin TG, Sim MS, et al. (2013) Better lactate clearance associated with good neurologic outcome in survivors who treated with therapeutic hypothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care 17:R260.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences