ISSN : 2576-3911

Integrative Journal of Global Health

A Case Study on the Application of Human Rights Principles in Health Policy Making and Programming in Cherang any Sub County in Kenya

Laila Abdul Latif1*, Faith Simiyu2 and Attiya Waris1

1School of Law, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

2Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Kenya

- *Corresponding Author:

- Laila Abdul Latif

Legal Practitioner and Law Lecturer at the

School of Law, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

Tel: +254713761217

E-mail: latif@uonbi.ac.ke

Received date: January 05, 2017; Accepted date: January 10, 2017; Published date: January 16, 2017

Citation: Latif LA, Simiyu F, Waris A. A Case Study on the Application of Human Rights Principles in Health Policy making and Programming in Cherang’any Sub County in Kenya. Integr J Glob Health. 2017, 1:1.

Abstract

This study examined the application of human rights principles in health policymaking and programming in Cherang’any sub-county. This sub-county has suffered from long standing discrimination and exclusion from the progressive realization of the right to health. Its residents continue to live on less than USD 1 a day. Under the burden of income and redistribution inequality and inequity, they lack readily and easily available, accessible, acceptable and quality healthcare and health systems. This has been as a result of failure by the national government to include them in participating towards the formulation and making of health policy and towards the implementation of health programmes at the sub-county level which reflects the type of healthcare the residents require following basic healthcare. Further, the lack of financial and administrative accountability, along with the lack of governance transparency in the provision of healthcare towards the residents of the sub-county, has in turn affected the health rights, opportunities and healthcare advancements available to them. Lack of basic infrastructure such as electricity, tarmac road networks, equipped medical facilities, water and lack of the means of transportation have further exacerbated the violation of their right to health. Accordingly, with the promulgation of the Kenyan Constitution in 2010 which seeks to advance socio and economic rights, the government committed to provide every citizen with the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to healthcare services including reproductive healthcare. In furtherance of this commitment, the government in 2013 developed its Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSPI) in order to entrench human rights principles in health policymaking and programming. This plan requires that healthcare be improved within the context of the human rights principles of accessibility, availability, affordability and quality of healthcare along with health financing, and participation of minorities. This study examined the extent to which these principles in health policymaking and programming have been applied in Chereng’any.

Keywords

Human rights; Health policy; Cherang’any sub county; Kenya

Introduction

In Kenya, the national and county governments are responsible for health policymaking and programming. The national government prepares a health policy, which the county governments later replicate at the county level [1]. As a result, most communities within the counties do not get to participate in health policymaking and programming since the drafting of the policy is left to the national government and the national level experts who may or may not consult these communities at the county or even sub-county level [2]. Hence, the policies and programmes do not reflect the healthcare needs of the communities at these levels. These communities include the poor, marginalised and vulnerable groups who as a result of not having participated in health policymaking, have no access to the decision makers and often even the policy document itself [3-9]. The inability to access information or participate in the decision making process also results in an additional obstacle of making it very difficult to not only hold the two levels of government accountable, but on what to hold them accountable for. Consequently, the communities cannot also demand transparency. Accordingly, in order to address these health rights challenges and to ensure that every citizen and community participates in health policymaking and programming, the national government in partnership with the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the GIZ under the German-Kenyan Health Sector Programme began to adopt a human rights based approach towards health policymaking in 2006 [10].

The objective of this programme was to improve equitable access especially for the poor and marginalized groups; specifically those affected by HIV/AIDS to affordable and good quality healthcare, particularly in the area of reproductive health [11-15]. To achieve this, the programme was divided into four key areas; (1) provision of policy advisory services so that the principles of human rights would be incorporated in health policymaking and programming; (2) health financing; (3) family planning and reproductive health; and (4) reduction of gender based violence and human rights violations. These areas were perceived as key to introducing a rights based approach into health. This programme was implemented in certain sub-counties as a pilot programme. Chereng’any however, was not among them. The evaluations and reviews of these pilot programmes that are running in the coastal areas of Kenya for example, have not yet been published by the GIZ. Nevertheless, the four key areas of the programme were subsequently introduced in the National Health Sector Strategic Plan (NHSSP II) and in corresponding health policy reforms following the promulgation of the 2010 constitution that decreed the application of human rights principles in the drafting and implementation of legislation. The Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSIP) is one such recent reform measure based on the four key areas identified by the German-Kenyan Health Sector Programme [16-20].

This plan has been replicated by the Trans-Nzoia county within whose administration Chereng’any is located. Since sub-counties rely on the plans developed by the county government which administers them, the key areas of the German-Kenyan Health Sector Programme are thus by extension implemented in Chereng’any by the sub-county government directly and through partnership with NGOs on specific areas. It is within this context that the objective of the study was framed. This raises a novel issue in understanding the implications of programmes developed at national level and introduced at county and sub-county level. It is novel in the sense that there have been no previous studies or research into the assessment of the application of human rights principles in health policymaking through the implementation of a program [21]. The German-Kenyan Health Sector Programme advanced the view that focus needed to be paid to certain critical areas towards achieving health rights and that these areas facilitated the introduction and subsequent application of human rights principles in health policymaking [22-24]. Hence, this programme is unique to Kenya and it is not known whether its salient features have been tried in other countries since there exists no data that is readily accessible in order to draw comparisons and assess its success. The study’s underlying objective, therefore, was to explore how the replication of this programme in Chereng’any by the sub-county government directly, and through partnership with NGOs has been successful in introducing and applying human rights to health policymaking and programming [25].

What gives this study a new insight compared to existing knowledge on human rights based approach to health policymaking and programming studies, is that it has observed how a programme limited in its scope such as the German-Kenyan Health Sector Programme towards ensuring equitable access to healthcare for the poor and marginalised mainly comprising of those affected by HIV/AIDS has resulted in a national wide adoption of a policy [26]. A policy that replicates its four key areas as the pillars upon which the objectives of a national health strategy have been developed in order to advance the inclusion of and application of human rights principles in health policymaking. Further, this is the first of studies from Kenya showing how the four key areas were translated into the creation of community health units which closed the discrimination gap that had persisted for so long in preventing communities from participating in the making of health policies [27-29]. The study points out how these community health units now act as an agent between the county and sub-counties in ensuring transparency and accountability, participation of the communities at subcounty level and eliminating the long standing discrimination in developing top down health policies. As such, the study shows how the application of human rights principles have overtime been accepted and applied into policymaking through the use of programmes in Cherang’any and as such provides a unique approach to understanding the application of human rights [30].

Methodology

An analytical framework was developed to conduct the research. This framework set out to investigate four thematic areas in examining the extent to which human rights principles are applied in policymaking in the context of (1) provision of policy advisory services so that the principles of human rights would be incorporated in health policymaking and programming; (2) health financing; (3) family planning and reproductive health; and (4) reduction of gender based violence and human rights violations [31-34].

Accordingly, the four thematic areas making up the analytical framework were as follows: (a) situation analysis based on the programmes implemented in Chereng'any to examine how human rights principles are being applied in the sub-county; (b) causal analysis to identify whether there exist any challenges in the application of these principles; (c) role analysis to highlight the obligations and duties of the government and Non- Governmental Organisations (NGOs) in advancing a human rights approach to health, and the level of community participation in health policymaking and programming; and (d) capacity analysis to examining the measures put in place to ensure that the communities in Cherang’any participate in health policymaking.

The results section lists out the responses gathered under each of these themes in a narrative form [35-37].

Information and evidence under these thematic areas was gathered through interviewing the government officials, health workers and officers of local NGOs, and holding focused group discussions with the community members at various health facilities. Interviews with the government officials was done in groups whereas individual interviews were held with officers of the local NGOs [38]. We also carried out both the focused group discussions and individual interviews with the health workers. Stakeholder consultations was done in focused groups. We also carried out physical observation of the health facilities. Each of the analyses took into consideration the extent to which the following human rights principles were applied in policymaking and programming; (i) non-discrimination; (ii) availability; (iii) accessibility; (iv) acceptability; (v) quality of health services; (vi) informed decision making about own health; (vii) privacy and confidentiality; (viii) participation in health policy and service decision making; and (ix) transparency and accountability [39,40].

The analytical framework was based on a case study approach employing the use of structured questionnaires used to conduct interviews and focused group discussions in Cherang’any. Part of the data collected was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics) 20 for Windows. The SPSS enabled the generation of quantitative data in the form of percentages. The other part of the data was collected through tape recordings of the interviews, note taking and through feedback provided by the interviewees who answered the questionnaires given. The study also combined the use of random and purposive sampling methods of data collection. Random for stakeholder consultations with the communities and purposive in selecting the health facilities to conduct the interviews. We also examined a number of documents provided to us by the government officials and NGOs during the interviews.

Findings

Situational analysis

Application of human rights principles through law and policy:

a. The constitution of Kenya: In reviewing the constitution we identified the following provisions of the supreme law of Kenya that provide for the right to health to be respected and protected;

Article 43 of the constitution of Kenya provides that every person has the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to health care services, including reproductive health care, and not to be denied emergency medical treatment. In the same article it provides for the determinants of health, including the right to accessible and adequate housing, reasonable standards of sanitation and adequate, acceptable food. It also provides for the right to clean and safe water in adequate quantities, to social security and to education [41].

Article 46 of the constitution gives consumers the right to protection of their health, safety and economic interests.

Article 53 of the constitution gives every child the right to basic nutrition, shelter and health care.

Article 21 of the constitution provides that ‘all state organs and all public officers have the duty to address the needs of vulnerable groups within society including women, older members of the society, persons with disabilities, children, youth, members of the minority or marginalised communities and members of particular ethnic, religion or cultural communities’. The constitution bars direct or indirect discrimination against any person on any ground including race, sex, pregnancy, marital status, health status, ethnic or social origin, colour, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, dress, language or birth [42].

Article 59 of the constitution establishes the Kenya National Human Rights and Equality Commission whose main function is to promote gender equality and equity generally and to coordinate and facilitate gender mainstreaming in national development [43].

Article 20 provides that in applying a provision of the Bill of Rights, a court shall adopt the interpretation that most favours the enforcement of a right or freedom and promote the values that underlie an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality, equity and freedom.

In applying the economic and social rights under Article 43, if the government claims that it does not have the resources to implement the right, it is the responsibility of the government to show that the resources are not available. In allocating the resources, the government is to give priority to ensuring the widest possible enjoyment of the right or freedom having regard to the prevailing circumstances, including the vulnerability of particular groups or individuals. Anyone can bring a suit to enforce his or her right to health when it is violated, directly or through other persons or civil society. There shall be no fee or a reasonable fee that does not impede access to legal proceeding, to avoid cost barriers [44].

b. Kenya Health Policy 2012-2030: Kenya has in place a health policy. This policy is developed around the following 5 objectives;

1. To eliminate communicable diseases;

2. To halt, and reverse rising burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs);

3. To reduce the burden of violence and injuries;

4. To minimize exposure to health risk factors; and

5. To strengthen collaboration with health related sectors.

These objectives are based on two strategies to be implemented at programme level; strategy one - to ensure quality and safe services, and strategy two-to ensure physical and financial access. The objectives are to further result in steering health policy towards 7 orientations. Orientations have been defined to mean policy direction that the health sector is to strive to attain with regards to investment [45]. These orientations are in relation to Health financing are;

Health leadership, Health products and technologies, Health information, Health workforce, Service, Delivery systems; and Health infrastructure.

Furthermore, these orientations are based on 6 human rights principles. These principles are; (a) participation; (b) people centred; (c) equity; (d) efficiency; (e) multi sectoral approach; and (f) social accountability. Hence, we conclude that there exists a basic legal framework to introduce and implement human rights principles in health policymaking and programming (Table 1). Whether these principles have been introduced in Chereng’any, we were able to assess through the various programmes implemented in the sub county as discussed in the next sub section [46-48].

Application of human rights principles through programmes: The German-Kenyan health sector programme: At the national level, this programme (hereinafter referred to as the “GK Programme”) laid the foundation for introducing human rights principles in health policymaking and programming. It led to the country adopting a human rights based constitution and further developing a national health strategy based on the four key areas identified by it as essential in introducing human rights principles in health policymaking and programming. These four areas concern; (1) provision of policy advisory services so that the principles of human rights would be incorporated in health policymaking and programming; we found that this area had been taken up by NAYA (see (d) below). (2) Health financing; we found that the sub county dealt with this area directly. (3) Family planning and reproductive health; we found that the implementation of this area had been taken up by AMPATH, CANA and NAYA (see (b), (c) and (d) below) and (4) reduction of gender based violence and human rights violations; we found that this area had been taken up by Trans-Nzoia Community Health Unit, AMPATH and CANA (see (a), (b) and (c) below). This was observed by examining the memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the NGOs and the sub-county [49].

Through the GK Programme, the interviews revealed that the county government authorized the setting up of community health units to further one or more of the four key areas. This we corroborated from the MoUs. These community health units sometimes collaborate for example with AMPATH to provide support in form of access to information and rights awareness to enable the community in Cherang’any to participate in policymaking processes. In furtherance of the objective of the GK Programme at Cherengany, AMPATH promotes advocacy forums on reproductive health issues, including gender based violence whereas KELIN, though not having permanent offices at Cherang’any, promotes advocacy for the rights of marginalised groups. A community health unit was also established to collect data and information from Cherang’any, to then participate in provision of policy advisory services, to provide access and availability of family planning and reproductive health as well as to reduce gender based violence [50].

a. Trans-Nzoia community health unit

During the interview with the Trans-Nzoia County Chief Officer for Health we were informed that the government, through the Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation (MOPHS) in pursuing the implementation of the fourth area of the GK Programme and to some extent the second area set up the Trans-Nzoia Community Health Unit to support delivery of healthcare at the community level. We visited this health unit and were shown its policy paper which we examined to find that its main objective is to enhance community access to healthcare and to make quality care available. Financial and technical support is given by AMREF Maanisha Programme, Afri Link which has trained 50 community health workers (CHWs) who are responsible to provide healthcare across Trans-Nzoia county within which Cherang’any is located. The CHWs collect data and give monthly reports to the in charge of Cherang’any Dispensary who forwards the same to the county.

A review of the reports provided during the interview showed that CHWs activities has seen increased number of women seeking reproductive health services in health facilities in Cherengany. The reports indicated that the number of women delivering their children in hospital has gone up and this has led to a reduction in maternal and infants deaths. According to our interview with the Sub County Director of Health CHWs have been instrumental in following up tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy (TB/ART) defaulters within the county including Chereng’any. Through their interventions in the community, we found that 30 tuberculosis drugs and 20 antiretroviral therapy defaulters were identified and are currently on medication and being cared for.

b. Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare Programme - AMPATH

In 2005, AMPATH established its offices in Trans-Nzoia county headed by a county coordinator. Its Cherang’any branch is headed by a sub-coordinator in charge of operations and programs in the constituency. This NGO focuses on persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) due to the high HIV prevalence rates in the year of its establishment. Of recent, AMPATH has began to expand its mandate to deal with diabetes and hypertension within Cherang’any and to support its existing health structures. According to the Trans Nzoia County Chief Officer for Health who during the interview showed us documents highlighting that AMPATH has been seen in promoting the right to health under the third and fourth areas of the GK Programme by having further developed the following programs in Chereng'any;

The HIV/AIDS program: During our field work we found that AMPATH has 22 anti-retroviral drugs providing sites within the county including Chereng’any. AMPATH stocks these sites with HIV/AIDS drugs available to the patients for free.

The Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission program (PMTCT): We read reports revealing that AMPATH carries out awareness programs in Cherang’any and trains mothers on how to securely breastfeed their infants in order to avoid HIV transmission [51].

The Orphans and Vulnerable Children Program. We read reports relating to this program which showed that the program targets orphans and vulnerable children in Cherang’any in order to ensure that they get an education and have a decent childhood. The reports indicated that the program provides free medical care to these children.

The Family Preservative Initiative. During the interview, the staff member indicated that this “is an economic empowerment program in Cherang’any that focuses on boosting the health of families providing certain initiatives that will enable a family to earn a living and therefore be able to afford medical care”.

The perpetual home testing and counselling program: At the interview it was also said that “this program focuses on carrying out door to door testing and counselling of community members”. The aim of this program we found was “that it is directed towards ensuring that every member of the community in Cherang’any is aware of their health status and be in a position to take proper care of themselves”.

AMPATH monthly reports showed that it serves over 20,000 patients in Chereng'any. It carries out continuous training and empowering health programs that are meant to improve health care in the public health facilities. The interview revealed that AMPATH works closely with the county government of Trans- Nzoia and Cherang’any sub-county to provide health services. However, in terms of health policymaking at county and national level AMPATH does not take part [52].

c. Community Action Network of Africa - CANA

The memorandum of understanding between CANA and the subcounty shown to us revealed that in order to implement the third and fourth areas of the GK Programme, CANA was authorised by the county government to work closely with sex workers, people living with HIV (PLHIV) as well as men having sex with men (MSM) in Chereng'any. Further examination of reports provided during the interview showed that with respect to sex workers, CANA has established a safe haven for them in order to protect those sex workers facing constant sexual violence and harassment by the police. CANA provides free testing and counselling services to sex workers and supplies them with condoms and lubricants. Further, CANA has also established a working group comprised of sex workers who occasionally meet to discuss the challenges they face and how to overcome these challenges the interview revealed. Reports prepared by CANA showed that it has aided sex workers in accessing medical services in health facilities. With respect to MSMs, CANA though aware of their existence finds it difficult to reach out to them. This is due to the secrecy with which MSMs operate based on their fear against becoming victims of violence and discrimination according to the interviewee. The interviews also revealed that the potential of CANA to reach out to heath workers in terms of educating them of the rights of the minorities is hampered due to a lack of financial resources and lack of support from the county government.

d. The Network for Adolescent and Youth in Africa - NAYA

Reviewing the constitution of NAYA showed that this is a youth led NGO working towards promoting adolescent and youth sexual reproductive health in Kenya. It has its main office in Nairobi but carries out media advocacy on reproductive health rights throughout Kenya including Trans-Nzoia. During the day that we spent at the NAYA office, we observed that NAYA advocates for the implementation of policies and legislation on adolescent and youth sexual reproductive health by disseminating information on issues concerning the right to health, and promoting adolescent and youth rights at national and community level. We discerned from the constitution shown during the interview that in Chereng’any, NAYA has worked in the pursuance of the third area of the GK Programme to develop the Adolescent Reproductive Health and Development Policy; it has designed advocacy programmes; trained health workers to provide adolescent-friendly health service; promoted skills training programmes to improve youth and adult partnership in achieving adolescent and youth sexual reproductive healthcare, and NAYA has also intervened at the community level to create legal awareness of health rights. According to the NAYA officer in charge of operations at Chereng’any, “NAYA has played a significant role in ensuring that the reproductive health rights for the youth and adolescent is available, accessible, affordable and acceptable”.

We identified from its evaluation reports (sections reproduced in quotation marks) that NAYA has intervened at the community level by implementing the following various programmes in order to promote access to sexual and reproductive health rights for adolescents and the youth.

Policy advocacy: Through this programme, “NAYA sensitises, mobilises the community in order to prepare them to be able to participate during stakeholder consultations made by the government when collecting public opinion on policymaking. To achieve this, NAYA works jointly with other networks and coalitions within and outside government to reach out to the community of Cherang’any which has a population of 226,306 inhabitants. Under this programme, NAYA has actively participated in developing the Adolescent and Reproductive Health Development Policy of 2003, the National Reproductive Health Policy of 2007, and the Reproductive Health Care Bill of 2014”.

Community education: NAYA through its programme titled “Participatory Education Theatre (PET)” “provides for community education towards awareness of sexual and reproductive health rights. PET uses the approach of visual arts through theatre plays and drama to sensitise the community on these rights. This approach is effective in the sense that it allows the community to actively participate in the theatre plays and drama thereby transforming them from passive spectators to active learners”.

Media-Advocacy. Under this programme NAYA having recognised the role and importance of media in promoting sexual and reproductive health rights works together with media houses “by providing them with useful information on these rights for dissemination. The aim under this programme is to use media houses to air debates on sexual and reproductive health rights and inform the listeners of organisations working in support of these rights”. Throughout the country, it was reported by the NAYA officer in charge of operations in Cherang’any that NAYA has been able to reach over five million people every year in disseminating information on the sexual and health rights through media houses.

Mentorship and Coaching. Under this programme NAYA “trains the youth under its Youth Leadership project. This project aims to train the youth with the necessary leadership skills enabling them to reach out to their peers in promoting sexual and reproductive health rights”.

e. KELIN

During the interview with the Executive Director of KELIN, he revealed that the NGO “is engaged in various programs aimed at sensitizing communities to respect, protect and promote health rights of Persons Living with HIV (PLHIV) in various counties including Cherang’any so that these communities can then participate in health policymaking”. In order to do this, we saw that KELIN had office space for providing pro bono legal training services aimed at educating PLHIV on their health rights. These training services are also for legal practitioners, NGOs and community members interested in advancing and protecting health rights of PLHIV. A review of KELIN’s project report showed that the aim of these trainings is to create legal awareness. Accordingly, we gathered from the minutes shown to us during the interview that KELIN has trained over 2000 health workers on legal, ethical and human rights issues in the context of health and some of these health workers have trained communities within Chereng’any.

Causal analysis: The problem of inadequate skills: Group based interviews with the Trans-Nzoia County Chief Officer for Health, Overall in Charge Lab Scientist, Sub County Director of Health and Trans-Nzoia County Medical Officer for Health revealed that despite the GK Programme areas being implemented through NGO support there was inadequate HIV/AIDS skills among Community Health Workers (CHWs) trained on community strategy developed by the government under which the Nzoia Community Health Unit was established. The community strategy training manual, they said at the interview, is shallow on matters of HIV/AIDS. Our review of the training manual showed that provisions on HIV/ AIDS were very sketchy and brief. During the interview, we were told that “this curriculum has led to production of ill equipped CHWs who are not able to provide palliative care to ailing persons living with HIV (PLHIV)”. That “with the growing cases of HIV/AIDS complications, these CHWs are not able to provide adequate care for people living with HIV/AIDS, and due to lack of training on home based care and support for bed ridden patients, many CHWs are in danger of getting infected with HIV and expose their clients to the danger of getting re-infected”.

The problem of inadequate health financing and infrastructure: During the interview with the Head of Research and Medical Coordination at the Ministry of Health, he stated that the second area under the GK Programme has been frustrated “as a result of inadequate health financing at the county level and more specifically towards Chereng'any". We examined the budget report shown to us with respect to the sub-county to verify that there was no adequate budget set aside for its health sector. Consequently, the national government, it was said at the interview “is ill equipped to support various hospitals within the community with the required basic items to facilitate effective delivery of basic health care services to the community at the house hold level”. The government is not able to provide the required basic care. For example, “the government is also not able to give staff uniforms, and identification badges to CHWs for use during their work in the community”. Further, a review of documents prepared by the Head of Research and Medical Coordination at the Ministry of Health for internal circulation showed that there are inadequate health facilities and services in Chereng'any yet the number of referrals by CHWs to the available health facilities within Chereng’any has gone up exerting a lot of pressure on facilities and health personnel. We were told that this has led to “frustration among residents and exhaustion of health personnel”. “Referral costs for AMREF Maanisha funded programmes in Cherang’any have gone up since clients are forced to seek health care in the neighbouring sub counties like Trans Nzoia West and Uasin Gishu districts”. We also saw that only two qualified doctors were present in all the health facilities that we had visited compared to the CHWs and nurses who made up the bulk of healthcare service providers. Furthermore, in Chepsiro Health Clinic we saw that one health worker served a population of approximately 5,000 people during our physical inspection. This was also confirmed by a statement during the interview.

With respect to shortages in medical supplies, we observed during our field research that medical supplies were usually stored in the county government’s office for distribution to the sub counties and we were informed by a health worker that as a result the supplies were stolen and sold to pharmacies and medical practitioners operating private clinics. This information was also corroborated by the Overall in Charge Lab Scientist for the Trans- Nzoia county during his interview. In our interview with the Sub County Director of Health, he informed us “that shortages in medical supplies were also due to a lack of understanding of the new system of devolved governance that had been introduced by Kenya's 2010 Constitution which mandated the transfer of functions from the national to the county government so that health care service provision was no longer a function of the national government but that of the county”.

Hence with the transfer of functions to the county, health workers were not cognizant on how to go about requisitioning for drugs through the county government and even when the drugs were requisitioned from those who knew how to do so, huge delays of up to six (6) months were witnessed before the drugs actually became available. We found this indicated in the internal memos shown to us by the Sub County Director of Health. Further, during our field research we found that at the various health facilities the medicines were stored in poor storage facilities, the medical equipments were equally stored in poor storage facilities and were at times outdated. Medicines at times expired due to a lack of electricity or fuel to keep the refrigerators working hence alternative methods of storage were being used such as use of water bottles donated by UNICEF or cold water boxes that somehow would keep the drugs at a suitable temperature.

Furthermore, we also measured that the nearest hospital in Chereng’any was about 10-20 kilometres away from the main community residences and the road towards the hospital from the residence areas was not tarmacked, it was hilly, steep and difficult to journey on except with a four wheel drive vehicle, a luxury not spotted in Chereng’any. However, we saw that 10 old and broken down ambulances support the entire Chereng’any and “are normally unavailable for use due to lack of fuel and lack of funds to purchase the fuel”. As alternatives, we saw that Chereng’any had purchased bicycles and motorcycles, but “because of the poor road conditions that are made worse with the rain, the bicycles and motorcycles purchased have sometimes added little value” revealed the interview with a nurse.

Health rights awareness: We saw only one health facility; Kaplamai Health Centre, providing information on what health rights mean. We saw that this information was displayed at the entrance to the facility for all to see. In all other health facilities we observed that the information displayed in the health facilities only concerned questions related to the period of treatments and the kind of medical services that were being offered at the health facilities.

The problem of marginalization in Cherang’any: We found the Sengwer as the marginalized community in Cherang’any during our road trip to Cherang’any when making physical inspection. We saw that the Sengwer community live in the hilly mountainous area of Cherang’any where the terrain is rough and difficult to access because of the poor road networks. The closest hospital to the Sengwer community we measured to be approximately 15-20 kilometres away accessible only on foot. This community is made up of approximately 3000 members. We observed that the community does not have any ambulances to cater for emergencies cases. However, we saw that a bicycle had been donated to the community to help transport the sick, however, the “bicycle proves futile in consideration of the distance to the nearest hospital and the fact that the cyclist may tire along the way”. This was mentioned to us during the focused group discussions. Their marginalization, we were told, is as a result of the following causes which were specified during the focused group discussions.

Lack of Identification Cards (ID): A majority of the Sengwer community do not have Kenyan identification cards. We asked during the discussions for those with IDs to raise their hands. No one did. The spokesperson stated that “this has impeded their ability to access services in Cherang’any where ID’s are required and has also restricted their ability to move freely in the country”.

Education: We find that the Sengwer community are unable to access education due to their location. We saw only one school in the vicinity. We were told that in 2007 a primary school was constructed for them in order to allow them to access education. The second school is in the process of being constructed. However, a majority of the population remains illiterate with no proper basic education.

Unemployment: The spokesperson at the interview stated that due to the lack of education, the Sengwer community have found it difficult to gain meaningful employment. We asked those present whether they were employed and we found that currently, no Sengwer is employed within the county government or in Chereng’any.

Property ownership: The Sengwer community live on the hills of Cherang’any and said that they “have no title deeds or documentation to show ownership of the land on which they have lived for years”. They said at the interview that this “makes them live in fear of eventual or forced eviction”.

Lack of water and water resources: We saw the community did not have any access to water be it piped or otherwise. This made the community prone to water-borne diseases according to an interview with a nurse. In another interview with the Sub County Director of Health we were told that “international donors have attempted to provide piped water to the community but the project remains stagnant to date”.

Poverty: We found the Sengwer community to be poor and largely dependent on subsistence farming to meet their daily needs. We were asked to give each person with as little as 10 Kenyan Shillings (approximately US$ 0.10) in order to buy basic commodities like soap.

Following our interview with members of the community, we also saw that they live about 15-20 kilometers away from the nearest hospital. The terrain to the hospital, is rocky, hilly and only accessible through a rough road that becomes impassable during the rainy season. The Sengwer are unable to access medical services offered at the hospital leading to the assumption by the majority of health care givers that their cultural practices and beliefs do not support modern medicine. This was mentioned to us in a number of interviews with the health workers. We saw that the Sengwer rely on traditional healers in order to mitigate the increasing incidences of diseases among them.

We observed that the nearest hospital to the Sengwer in an effort to make health services more accessible and available to them has engaged community health workers (CHW) who work in partnership with one nurse in order to address the rising health concerns of the Sengwer. According to the Sengwer, ‘this approach has to some extent addressed the issue of access to health services for them” they said during the discussions.

Further, we gathered during the discussions that as a result of their unemployment and high poverty level status, the Sengwer have not been able to access all the available services at the hospital in Chereng’any. This is because, not all the health services offered at the facility are free of charge. We saw that most of the health services are chargeable and therefore, members of the public must pay for them in order to be served. We reviewed the policy papers of the health facilities and saw that the hospital has a waiver system. When we asked the Sengwer why they do not utilize the waiver, they complained that the system rarely works. We read that under the waiver system, persons seeking health services but are unable to pay for them, are required to fill a waiver form indicating their inability to pay for the services. Once the waiver form has been filled, it is taken to the hospital management, who exercise its discretion in granting the waiver. The Sengwer informed us that they acknowledge that while the system is commendable it cannot address all their health concerns.

We saw that a clinic is being constructed within the Sengwer’s market place. We were told that the clinic has been under construction since 2007 but due to insufficient funds, the process has been slow. Following the adoption of a devolved system of governance in 2010 by the Republic of Kenya, the Sengwer alleged during the discussions that the county government has taken no interest in the project thereby neglecting their right to have access to health services.

Role analysis

The role of the government: In the interviews carried out with the Trans-Nzoia County Chief Officer for Health, Overall in Charge Lab Scientist, Sub County Director of Health and Trans- Nzoia County Medical Officer for Health they said that the new form of governance that the country has adopted following the promulgation of the 2010 constitution “has caused legal challenges in the understanding of responsibility allocation towards the provision of healthcare and health services at county level”. They further mentioned that the lack of a uniform health law further “exacerbates the problem of lack of a clear direction on providing communities access to healthcare”.

We were also informed that the community members in Cherang’any do not individually participate in the making of health policy or towards the implementation of health programs. We noted that Chereng’any had not yet implemented laws relating to public participation and that the health policy that existed was entirely replicated from the national policy that was prepared without consultations at grassroots levels. However, the health centres, dispensaries and hospital in Chereng’any “are the medium through which the county and national government become aware of their healthcare challenges and concerns”. Through these mediums “we have the responsibility towards informing our patients of their right to privacy and confidentiality and to provide them with adequate information with which to make informed decisions on their healthcare”.

The interview also revealed that as a result of devolution the staff in the public health facilities in Cherang’any are not familiar with change in the administration of the facilities. “Prior to devolution, the national government was responsible for distributing medical supplies such as drugs and necessary equipment, following devolution the obligation shifted to the counties and most of the shortages in the supplies of medicines and equipment is a result of the health worker in charge of administration failing to have made the requisition for procurement”.

Through reviewing documents provided to us we noted that in discharging its duty to the communities making up the entire county and not just Chereng’any, the county government having acknowledged the challenges the area faces in realisation of the right to health, is considering to take measures in order to pursue a human rights based approach towards health policymaking and programming.

With respect to the extent of awareness by the community members of human rights principles in health policymaking and programming the following findings were made.

Extent of awareness of the human rights principles:

a. The human right principle of non-discrimination

We asked the respondents to indicate who in their opinion was responsible for ensuring that there was no discrimination in the provision of healthcare in Cherengany. The following was their response in terms of percentages; 23% of the respondents attributed the responsibility to county leaders, 33% attributed it to health workers, and only 12% attributed it to the community members while 28% said it was the responsibility of everyone to ensure that there was no discrimination in the provision of healthcare.

b. The human right principle of participation

We asked the respondents to indicate whether they regularly took part in identifying the health needs in their area on a regular basis. The following was their response in terms of percentages; 50% affirmed they regularly participated while 50% said they did not. Stakeholder consultations with the Chereng’any community revealed that the Sengwer did not regularly participate in identifying their health needs. 86% of the respondents from Kapsara Health Centre affirmed that they participated in identifying their health needs.

On whether community health meetings are held during the best time of the day with all residents being put into consideration in order to collect their views in relation to the provision of healthcare services; 28% of the respondents agreed, 47% strongly agreed, 1% did not know, 21% disagreed and only 2% strongly disagreed.

Respondents were asked to indicate whether the sub-county encouraged them to take part in health programmes, 79% of the respondents agreed, 20% disagreed, and 1% did not know whether the sub county encouraged them to participate in health programs. 43% of the respondents agreed, 35% disagreed, and 10% were not sure in getting involved and interested in taking part in health programmes.

79% of the respondents agreed that county leaders supported and encouraged them to participate in health programmes, 20% disagreed and 1% did not know whether county leaders encouraged them to participate in health programs.

c. The human right principle of transparency and accountability

We asked the respondents to indicate whether they were aware of the concept of the right to health, 60% answered yes whilst 37% answered no and only 2% did not know. On being asked to list their familiarity with the right to health 3% did not list any response, 33% were not conversant with what this meant, 43% were fairly conversant with the right to health and only 22% were fully aware of these rights.

On being questioned as to whether every community member had a chance to voice his or her health needs, 12% of the respondents strongly agreed, 62% agreed, 16% strongly disagreed, 5.6% disagreed, 2% did not know and 1% remained unknown. Respondents were also asked to indicate whether community leaders regularly asked them to forward their health needs in order for them to be addressed, 27% of the respondents strongly agreed, 39% agreed and 29% strongly disagreed.

However, 7.6% of the respondents agreed, 28% did not know and 64% disagreed in their response to the question on whether all the contributions and suggestions on healthcare improvement made and suggested by them are listened to and acted upon. Further, 27% agreed, 43% strongly agreed, 28% disagreed and 1% strongly disagreed in their answers as to whether they were given information about the manner in which their health needs concerns and complaints were being addressed.

We asked the respondents to indicate whether county/ community/village leaders were always available and willing to take action on their health demands. The findings revealed that 50% agreed that they were available and willing to take action on their health demands, 49% disagreed and only 1% remained unsure.52% of the respondents felt that their complaints were forwarded to the government by health workers; 40% felt that the county health officer was responsible; 6% felt that the responsibility lay with the community leaders while 2% has no answer. 54% of the respondents were aware of the persons responsible for forwarding their complaints to the government whereas 43% did not know the persons responsible and 3% remained unsure.

d. The human right principle of informed decision making on own health

We asked the respondents to indicate whether they were provided with adequate information in order to make an informed decision on their own health. 11% affirmed this question, 50% of the respondents reported that it was the health workers who made the decision, 3% stated that they were not sure whereas 33% reported that it was a joint decision made with a health worker.

e. The human right principles of AAAQ

61% of the respondents believed that there were healthcare needs and services within Cherang’any that were not available, accessible, acceptable and of quality, 38% of the respondents believed otherwise and 1% were not sure.

On the health problems that need to be addressed urgently, the respondents stated; malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, cervical cancer, diarrhoea diseases in children, complications of female genital mutilation (FGM) during delivery and pneumonia in children.

On healthcare service challenges that need to be addressed, the respondents cited; financial constraints within the health facilities, infrastructural problems such as lack of medical equipments, bureaucracy and lack of specialised medical care due to insufficient number of medical personnel.

60% of the respondents reported in having experienced difficulties in accessing health services, and 40% stated that they were not sure. 7% of the respondents indicated having complained to community leaders and health workers about experiencing difficulties, 13% stated that they made no complaints and 80% provided no answer. 13% stated that the complaints made by them had been ignored and 87% of the respondents provided no answer.

Obstacles to accessing healthcare services were identified as financial where healthcare was not provided for free and poor infrastructure; primarily poor road network.

f. The human right principle of privacy and confidentiality

12% of the respondents indicated that they feared making complaints about their health concerns to the government or health facility. 11% stated that they felt secured as a result of their right to confidentiality and 77% were not sure. 1% cited personal reasons for fear in making complaints, 2% stated that they lacked confidence as to whether their complaint would be heard, 28% reported that the subject of the complaint was sometimes the person responsible for complains and 69% of the respondents provided no answer (Figure 1).

Capacity analysis

On capacity with respect to health financing, interviews with the Trans-Nzoia County Chief Officer for Health, Overall in Charge Lab Scientist, Sub County Director of Health and Trans-Nzoia County Medical Officer for Health revealed that majority of the funds allocated to the county by the national government are used up in paying remuneration and allowances instead of investment in the procurement of technology and equipment required towards providing quality healthcare. This information was verified by reviewing the minutes shown of meetings held within the county concerning the health budget. The budget allocated to the health sector for Trans-Nzoia county we saw was KSHS 742,288,300 (approximately USD 8,247,648). This amount we saw was divided between the 5 sub-counties under the administration of the county. These sub-counties are Chereng’any, Kwanza, Saboti, Endebess and Kiminini. The total amount however, we were told is distributed to the county by the national government in instalments thereby impeding the development of long term plans by the county. We found this information corroborated by the Head of Research and Medical Coordination Unit at the Ministry of Health. The county in turn distributes the allocated funds to its sub-counties in instalments as well. This information was revealed by the Sub County Director of Health. Our group based interviews together with physical inspection with the health workers in the following facilities revealed that:

Cherang’any lacked electricity in various health centres despite an existing agreement with the Kenya Power and Lighting Company (KPLC) not to disrupt electricity transmission in health centres. We were not shown this agreement. It was only mentioned during the interviews.

Sitatunga Dispensary in Cherang’any received at least 100 patients per day, but faced the following challenges; (1) drugs shortages. The dispensary had empty fridges with no drugs to give its patients. As a result, it had to had to refer them to other health facilities located several kilometres away; (2) staff shortages. The dispensary has only 8 staff members. Two nurses, one clinical officer and the rest are support staff; and (3) lack of proper infrastructure. The dispensary is sometimes forced to handle medical issues beyond its scope. We had the chance to witness these facts firsthand.

Cherang’any Sub County Hospital developed a community outreach program. During our inspection of it, we found that the hospital has been functioning without electricity. We were told since November 2014, the hospital has been functioning without power. We saw that foundations were being laid to construct an in-patient centre. Having looked at the hospital’s budget towards the construction of the in-patient centre and the general running of the hospital we saw that the financing was not adequate.

Chepsiro Clinic is located about 20 km from Cherang’any Sub County Hospital. It also faces a number of challenges such as; (a) staff shortage. We saw that the clinic has only two nurses who attend to over one hundred (100) patients a day. At the time of interview there was only one nurse attending to over thirty (30) patients who had visited the facility that morning and because of lack of funding, the county has been unable to increase the staff number at the facility; (b) poor road network. We had difficulty accessing the facility due to the poor state of roads. The main road from Cherang’any Health Centre is in a state of disrepair, the tarmac is no longer there and as has become almost impassable, making a distance that could be covered within 30 minutes to take over 1 hour 30 minutes by car. From the main road, there is a murram road that becomes impossible to use during rainy seasons. We observed that in the area where a majority of the population are poor peasant farmers, they covered this distance by foot; and (c) incomplete infrastructure development. At the clinic, a project was initiated in 2011 by a former a Member of Parliament to construct a maternity section. The project has since stalled due to lack of funding and as such the clinic we observed has had to make do with rooms that are not properly suited to offering maternal services for delivering mothers (Table 1).

| Treaty | Date signed/ratified |

|---|---|

| Universal Declaration on Human Rights | July 1990 |

| Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) | 1997a |

| International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) | May 1972a |

| Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979) | 1984a |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) | 1986 |

| International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of race discrimination (1966) | 1971a |

| African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1990) | Jul-96 |

| Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (2003) | December 2003* |

*means signatory only, ‘a’ means accession

Table 1: Factors of emission of different fuels. Source: IDAE and REE.

Kaplamai Health Centre receives over 150 patients per day. Some of the challenges experienced by the centre we saw also include; (i) staff shortage. The centre has 15 staff members. These include 9 nurses, 1 clinical officer, 3 public health officers, 1 lab technician and 1 nutritionist. It has no trained doctor; and (ii) shortage of drugs. At the time of the interview, the centre had no drugs available. This shortage had been in consistent for the past two months it was revealed during the interviews.

Table 2 captures the findings following our interview with the Trans - Nzoia County Executive. The County Executive revealed that the whole county and not just Chereng’any sub-county was facing challenges in four critical areas that have gone unaddressed due to poor administration and lack of financial resources. He provided us with a number of documents for internal circulation that were referred to during the interview (Table 3).

| Areas facing challenges | The specific challenges faced |

|---|---|

| Appropriate and equitably distributed health workers | Inadequate numbers of health workers in post |

| Lack of skills inventory | |

| Skewed distribution of health workers with significant gaps in rural areas | |

| Lack of budgetary support to enhance recruitment | |

| Attraction and retention of health workers | High level of attrition |

| Unfavourable terms and conditions of work | |

| Lack of incentives for hard to reach areas | |

| Improved but disharmonies remuneration | |

| Lack of equity in remuneration of health workers | |

| Low employee satisfaction level | |

| Stagnation due to unfavourable career guidelines | |

| Institutional and health workers performance | Lack of adequate functional structures to support performance |

| Weak staff performance appraisal | |

| Leadership and management capacities not institutionalised in all service delivery post | |

| Training, capacity building and development of health workers | Skills database for health workers is not available |

| Inadequate facilities for training | |

| Lack of training funds | |

| Lack of policy guideline on competencies and skills required for specific cadres. | |

| Lack of knowledge on devolved governance especially as it relates to health care services |

Table 2: Health Sector Challenges.

| Key Health Infrastructure | Primary care facilities | Hospitals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dispensaries | Health Centres | Medical Clinics | Nursing Homes | ||

| Government | 36 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Faith based | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| NGOs | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Private | 0 | 0 | 26 | 3 | 0 |

Table 3: Key Health Infrastructure Throughout Trans-Nzoia County.

The Trans-Nzoia County Chief Officer for Health further referred us to reports prepared by his office; a breakdown of which is shown in Table 4 below of the distribution of health infrastructure across the entire county highlighting the gaps in infrastructure that prevent access and availability of healthcare. These gaps, however, are being addressed at policy level.

| Health inputs & processes | No. available | No./10,000 persons | Required numbers | Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| County level | ||||

| Physical Infrastructure | ||||

| Hospitals | 4 | 0.5 | 9 | 5 |

| Primary Care Facilities | 48 | 0.5 | 95 | 42 |

| Community Units | 138 | 1 | 190 | 52 |

| Full equipment availability for | ||||

| Maternity | - | - | - | - |

| MCH / FP unit | 52 | No data | - | |

| Theatre | 1 | No data | 9 | 7 |

| CSSD | 1 | No data | 15 | 13 |

| Laboratory | 1 | No data | 52 | 51 |

| Imaging | 1 | No data | 9 | 8 |

| Outpatients | 52 | No data | 52 | 0 |

| Pharmacy | 52 | No data | 52 | 0 |

| Eye unit | 1 | No data | 9 | 8 |

| ENT Unit | 1 | No data | 9 | 8 |

| Dental Unit | 1 | No data | 9 | 8 |

| Minor theatre | 13 | No data | 15 | 2 |

| Wards | 13 | No data | 15 | 2 |

| Physiotherapy unit | 2 | No data | 9 | 7 |

| Mortuary | 2 | No data | 10 | 8 |

| Transport | No data | |||

| Ambulances | 6 | No data | 16 | 10 |

| Support / utility vehicles | 5 | No data | 25 | 20 |

| Bicycles | 401 | No data | 4750 | 4349 |

| Motor cycles | 79 | No data | 205 | 126 |

Table 4: Distribution of Health Infrastructure Across Trans-Nzoia County.

We were shown draft plans highlighting that at the policy level the county government is preparing a strategic and investment plan for health for the county and its sub-counties. With respect to consulting the communities in order to develop a socially inclusive and participatory health policy, the staff at the office of the Trans - Nzoia County Executive in separate interviews referred us to documentation showing the level of performance by the county government in meeting its targets towards introducing a participatory approach to health policymaking. We list the results in the Tables 5 and 6 below.

| Intervention | 2013 total | 2013 targets | Performance % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Facility Health Management Teams meetings held in 2013 (data not available for 2014) | 216 | 648 | 33.3 |

| 2 | Quarterly stakeholder meetings held in 2013 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| 3 | Annual Operational Plan available for 2013 | 54 | 55 | 98.1 |

| 4 | Annual stakeholders meeting held for past year 2013 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 5 | Facility committee meetings held in 2013 | 216 | 216 | 100 |

| 6 | Sub County Health management team meetings for 2013 | No data | No data | - |

Table 5: Targets to Enable Participation of Stakeholders in Health Policymaking and Programming.

| Intervention | 2013 total | 2013 targets | Performance % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Outreaches carried out | 650 | 1,296 | 50.2 |

| 2 | Therapeutic Committee meetings held in past 12 months | 1 | 16 | 6.3 |

| 3 | Patient safety protocols / guidelines displayed in facility, and are being followed | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 4 | Health service charter is available, and is displayed | 23 | 54 | 42.6 |

| 5 | Emergency contingency plans (including referral plans) available | 47 | 54 | 87.0 |

Table 6: Targets to Raise Awareness and Involve Community in Participation.

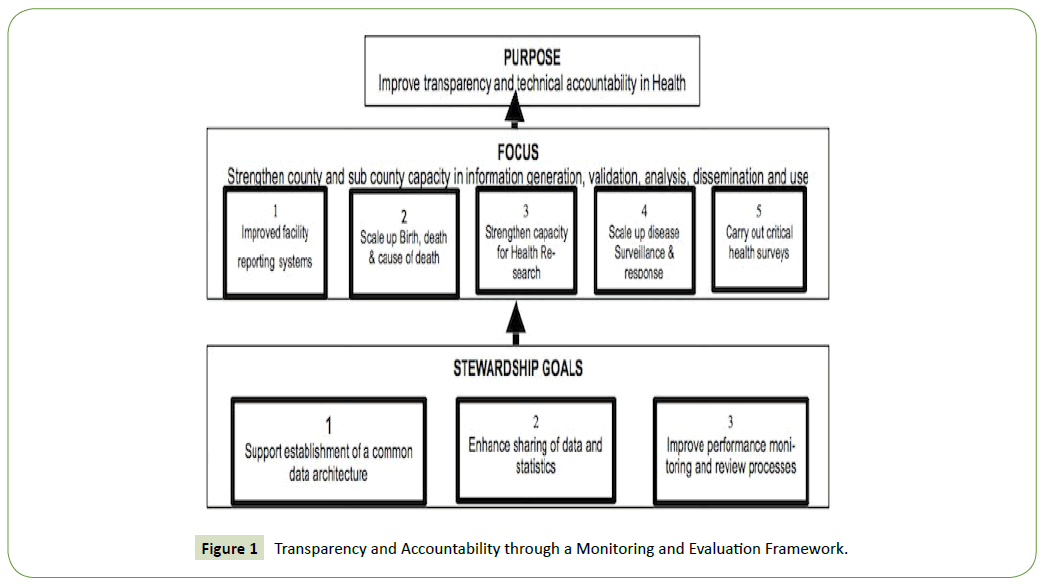

In improving transparency and accountability, we were shown a monitoring and evaluation framework that the the county government has developed to be utilised by Chereng’any and other sub counties.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine the application of human rights principles in health policy making and programming for Chereng’any sub-county. The Kenyan government has committed to provide every citizen with the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to healthcare services including reproductive healthcare. This commitment was to be realised through the adoption of human rights principles in health policymaking and implemented through health programmes. Accordingly, the government developed the Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSPI) in order to entrench human rights principles in health policymaking. This plan identified the principles as those of accessibility, availability, affordability and quality of healthcare along with health financing, and participation of minorities.

Hence, in order to test how these principles, including the principles of transparency and accountability, informed decision making about own health and non discrimination are applied in health policymaking at Cherang'any sub-county level, we undertook to conduct interviews with various NGOs providing services that related to the four key areas of the German - Kenyan Health Sector Programme and we found that the principles were applied through the implementation of programmes. Programmes to sensitize people and make them aware of their health rights, programmes where free medicines were provided, programmes related sexual reproductive rights and protection against bender based violence. We identified several health programmes that had been implemented in Cherang’any that advanced and promoted the right to health. We also interviewed government officials, health workers and community members of Cherang’any to gather their views and experiences in understanding how human rights priniciples were applied in health policymaking and programming. Health workers during these interviews expressed concern at the inadequacy of the current healthcare system as a result of lack of finances, which to them proved detrimental towards the government’s obligation to provide its citizens with the right to health which was available and accessible. This was seen from the shortages of health workers and essential medicines.

The government has put in measures to ensure that the human rights principles are protected by law and policy on one hand and applied through health programmes on the other. The programmes have come a long way in ensuring access to medical services and availability of drugs, and creating awareness so that residents are able to make informed decisions related to healthcare. In Chereng’any NGOs stand in for the sub-county government in creating awareness of rights and ensuring that the residents participate in various programmes carried out by the NGOs. Despite this the NGOs do not take part in health policymaking. They only aid the sub-county government in providing healthcare to the marginalized population.

We tested the study’s objective by grouping our research into four themes under the headings; situational; causal, role and capacity analyses. These analyses confirmed that the human rights principles were an integral part to health policymaking and that their application depended on programmes implemented at the county and sub-county level. Accordingly, we found that the programmes implemented in Chereng’any were evidences of success in terms of providing access to healthcare information, and in adequately informing the community members of their right to health, which in turn prepared them to participate towards voicing their health concerns. These programmes also provided access to health care for sexual and reproductive health, and provided quality free medical care and supply of essential drugs for persons affected by HIV/AIDS and various communicable diseases. Since some of these programmes were involved in providing policy advice to the county government they ensured transparency in, and accountability of, the health policymaking process.

Our findings also showed that the 4 key areas; (1) provision of policy advisory services so that the principles of human rights would be incorporated in health policymaking and programming; (2) health financing; (3) family planning and reproductive health; and (4) reduction of gender based violence and human rights violations, of the German - Kenya Health Sector Program facilitated the application of human rights principles in health programming. The four areas were found to have been implemented in Chereng’any by various NGOs focused on promoting a human rights based approach towards health. Consequently, the principles of human rights in health programmes were found to be effectively applied by NGOs. The county government was found to have endorsed the principles at policy level. However, the application of these principles in practice we found to be constrained as a result of (1) lack of finances; (2) shortages of staff; (3) lack of qualified staff; (4) shortages of essential medicines; (5) lack of a health policy specific to Chereng’any; (6) a top down approach in decision making; and (7) lack of monitoring and evaluation of public hospitals and dispensaries in the provision healthcare services.

We also found there to be a mismatch between what the focused group discussions with the Sengwer communities, certain health workers and the interviews with the Tranz - Nzoia County Executive officer revealed. The former indicated that their right to health was not fully being provided by the government wheres documentation showed that the government was making progress in realising the right to health. The fact that structures are in place does not necessarily mean that the right to health of the people is being met when concerns such as shortages of health workers and essential medicines were found to be rampant. Hence, in the effective application of the principles of human rights structural transformations in order to have good roads, electricity, water and transports systems are most relevant and necessary.

Further, this study reiterates that the lack of financial and administrative accountability, along with the lack of financial and governance transparency in the provision of healthcare towards the residents of the sub-county has impacted on their health rights, opportunities and healthcare advancements available to them. Lack of basic infrastructure such as electricity, tarmac road networks, equipped medical facilities, water and lack of the means of transportation are challenges towards the full application of human rights principles in health at Chereng’any. This shows that the underlying determinants play a key role in achieving the right to health and the sub-county must address these infrastructure related concerns. We also found that Chereng’any does not have its own health strategy or policy. Instead it relied on the health strategy of the Trans - Nzoia county government within whose administration it is located. The county government simply replicated the KHSSPI. We found this to be detrimental towards achieving the application of human rights principles in health policymaking since relying on polices developed at different governance levels means that the specific needs and concerns of people at the grassroots is excluded. Hence, we recommend that in order to fully integrate a human rights based approach towards health, Chereng’any must develop its own health policy in consultation with the community and local NGOs, operate within the principles of fiscal responsibility in distributing its health budget across its health sector and employ a bottom up approach in developing and authorising the implementation of programs that aim to protect, promote and preserve the right to health.

On limitations we found that the limited resources and time available constrained the study team to spend more time conducting interviews. The study team was able to visit with great hardship because of the terrain, a few hospitals in Chereng’any. The lack of resources was evident from the fact that we could not hire four-wheel vehicles and resource persons familiar with the terrain but had to rely on mobile phone communications to traverse the terrain in order to get to the heath facilities and communities. However, we acknowledge and are grateful to the WHO for providing us with funds to carry out our research and meet our travel expenses.

Conclusion

The German-Kenya Health Sector Programme began to introduce human rights principles into health policymaking. This led to the government adopting a health sector strategy which was replicated at county level. Further, the strategy led to sub-counties, such as Chereng’any adopting a human rights approach towards its health programmes at public facilities and in partnership with community health units. NGOs also took up a human rights based approach towards providing healthcare and raising awareness. Hence, in Chereng’any the application of human rights principles into health have been done through the implementation of programmes. However, rights require resources and without adequate financial resources the extent to which human rights principles are applied into health policymaking and programming are constrained. Investment in infrastructure and finance, supported by Chereng’any developing its own health policy and including the community members in the implementation of programmes is therefore key towards full application of the human rights principles. Collaborating through partnerships with the NGOs may address the financial gaps in terms of soliciting for financial aid as well as training of more community health workers to access the Sengwer and other community members.

What gave this study a new insight compared to existing knowledge on human rights based approach to health policymaking and programming studies, is that it has observed how a programme limited in its scope such as the German-Kenyan Health Sector Programme towards ensuring equitable access to healthcare for the poor and marginalised mainly comprising of those affected by HIV/AIDS has resulted in a national wide adoption of a policy that replicates its four key areas as the pillars upon which the objectives of a national health strategy have been developed in order to advance the inclusion of and application of human rights principles in health policymaking. Further, this is the first of studies from Kenya showing how the four key areas were translated into the creation of community health units which closed the discrimination gap that had persisted for so long in preventing communities from participating in the making of health policies. The study points out how these community health units now act as an agent between the county and sub-counties in ensuring transparency and accountability, participation of the communities at sub-county level and eliminating the long standing discrimination in developing top down health policies. As such, the study shows how the application of human rights principles have overtime been accepted and applied into policymaking through the use of programmes in Chereng’any and as such provides a unique approach to understanding the application of human rights.

Chereng’any ought to have its own health strategy or policy. Instead of relying on the health strategy of the county government within whose administration it is located. The county government simply replicated the KHSSPI. This is detrimental towards achieving the application of human rights principles in health policymaking and programming since relying on polices developed at different governance levels means that the specific needs and concerns of people at the grassroots is excluded. Finally, in order to fully integrate a human rights based approach towards health Chereng’any must develop its own health policy in consultation with the community and local NGOs, operate within the principles of fiscal responsibility in distributing its health budget across its health sector, employ a bottom up approach in developing and authorise the implementation of programs that aim to protect, promote and preserve the right to health.

References

- Republic of Kenya, Constitution of Kenya (2010) Fourth Schedule. Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Interview with the Head of Research and Medical Coordination Unit at the Ministry of Health.

- KEMRI-Welcome Trust Research Programme, Mustang Management Consultants, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Training and Research Support Centre (2011) Equity Watch: Assessing Progress towards Equity in Health in Kenya, KEMRI, EQUINET, Nairobi and Harare.

- Vision 2030: Sector plan for health 2008-2012 (2008) Ministry of Medical Services (MoMS) and Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation (MoPHS), Government of Kenya.

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), Development of the Health Sector, Kenya (2005-2016).

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), Healthy Developments.

- Latif L, Simiyu F(2015) Interview with the Head of Research and Medical Coordination Unit at the Ministry of Health.

- Latif L, Simiyu F (2015) Interview with an official from the GIZ Kenya Health Sector Programme.

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health. Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSPI) July 2013-June 2017. Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya.

- WarisW, Latif L (2015) Legal and Financial Responsibility in Promoting Health Equity in Kenya. JKUAT Law Journal1: 2015.

- Republic of Kenya, Trans-Nzoia County Government. Trans-Nzoia Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan, Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya.

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (MZ), Development of the Health Sector, Kenya 2005-2016.

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health. Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSPI) July 2013 - June 2017. Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Republic of Kenya, Constitution of Kenya. 2010. Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Ministry of Medical Services and Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, The Kenya Health Policy 2012-2030, Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya.

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), Healthy Developments.

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health. Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSPI) July 2013-June 2017. Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Latif L, Simiyu F(2015) Interview with the Tranz-Nzioa County Chief Officer for Health.

- Tranz-Nzoia Community Health Unit reports prepared by the Tranz-Nzoia County Chief Officer for Health as part of the health sector audit.

- Latif L, Simiyu F(2015) Interview with legal officer for AMPATH.